Guest post by Jay Dugad

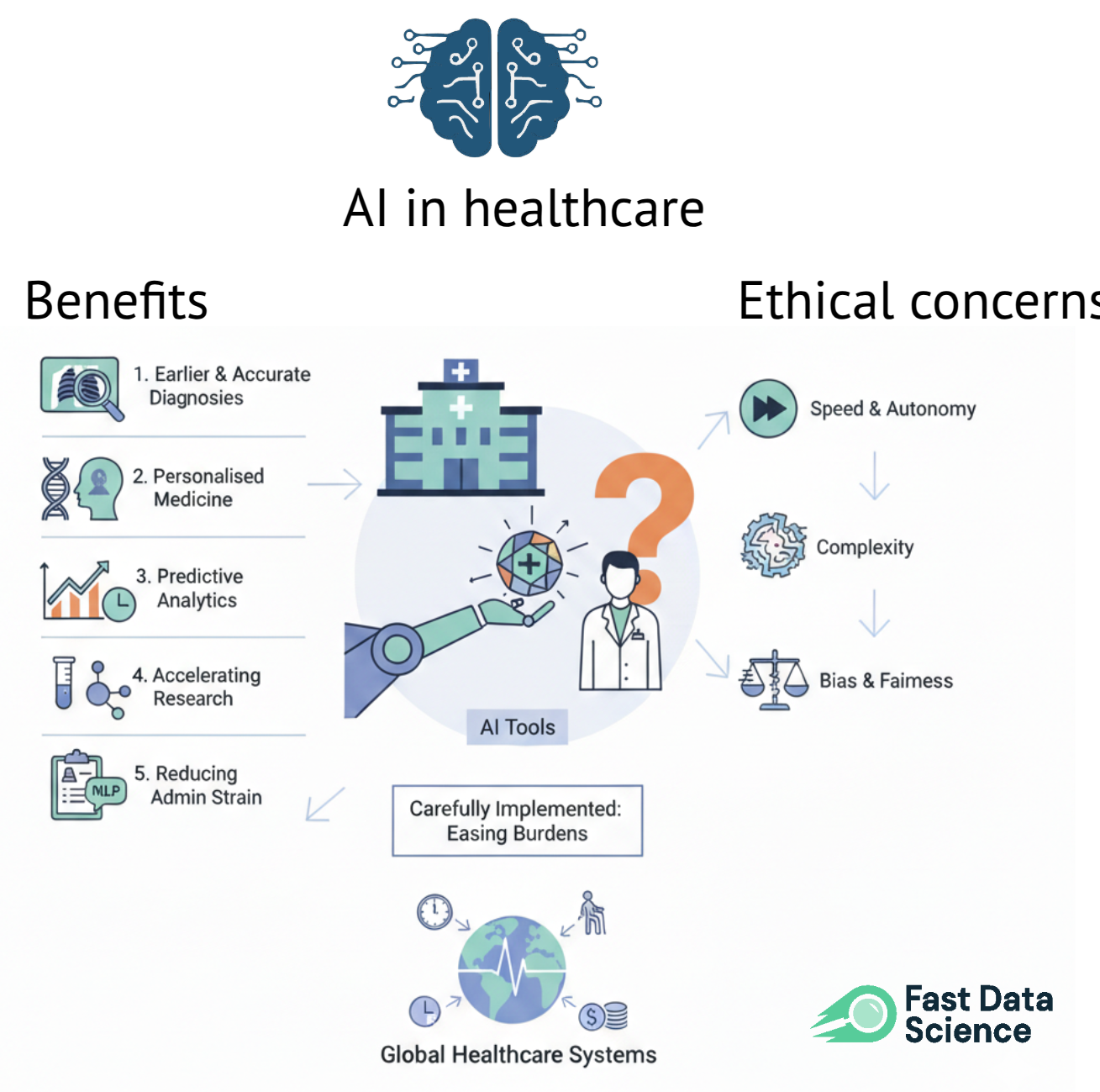

Artificial intelligence has become one of the most talked-about forces shaping modern healthcare. Machines detecting disease, systems predicting patient deterioration, and algorithms recommending personalised treatments all once sounded like science fiction but now sit inside hospitals, research labs, and GP practices across the world.

With this rapid adoption comes an equally rapid rise in difficult questions. How far should AI go? Who gets to decide what is ethical? And how do we protect patients while still embracing the advantages these technologies promise?

AI systems are already influencing real diagnoses, triage decisions, drug discovery timelines, and national healthcare strategies. AI systems can be more dynamic and unpredictable than traditional medical devices. That uncertainty forces us to rethink long-standing ethical principles such as trust, accountability, and fairness.

This blog explores both sides of the conversation: the extraordinary opportunities AI brings to healthcare, and the equally significant risks that require thoughtful regulation, transparency, and oversight.

Healthcare systems across the globe are facing mounting pressure: ageing populations, stretched workforces, long patient backlogs, and rising costs. When carefully implemented, AI offers tools, that can genuinely ease some of these burdens.

AI systems trained on medical imaging now detect certain cancers, retinal issues, and cardiovascular abnormalities with accuracy rivalling — and in some cases surpassing — human experts[1]. A well-designed model doesn’t get tired, doesn’t overlook subtle anomalies, and can review thousands of scans faster than any clinician.

Instead of one-size-fits-all treatment pathways, AI can analyse genetics, lifestyle data, medical history, environmental factors, and behavioural patterns to recommend care that is personal and often more effective[1].

Hospitals are increasingly using AI to forecast patient deterioration, emergency department surges, bed shortages, and high-risk complications such as sepsis. These predictions give clinicians valuable time — time that can make the difference between life and death.

Drug discovery, which previously relied on years of lab work, now benefits from AI models that screen potential molecules, simulate binding interactions, and predict toxicity even before the first laboratory experiment begins[3].

In the NHS and similar public systems, clinicians routinely lose hours to note-taking, scheduling, and paperwork. Natural language processing (NLP) tools can automatically summarise consultations or generate discharge notes[2].

All these advantages make AI a tempting addition to hospitals and health organisations.

However, the same strengths that make AI powerful — speed, autonomy, and complexity — also raise difficult ethical concerns.

Opportunities of AI in Healthcare

While the potential is enormous, healthcare is not a sandbox where technology can be tested without consequences. Decisions made by AI systems can directly affect human lives, sometimes subtly, sometimes dramatically. Ethical concerns arise not only from the technology itself, but also from how institutions choose to deploy it.

Bias in AI is a documented problem in deployed systems.

Because AI learns from data, it inherits any imbalance or bias hidden within that data. Obermeyer et al.[4] documented how a widely used US hospital algorithm assigned lower risk scores to Black patients due to flawed assumptions in its training data.

Examples of AI bias in healthcare include:

These biases often go unnoticed until real patients are harmed, raising serious questions about responsibility, representation, and equity.

Clinicians justify their decisions through evidence and reasoning. AI systems, however, often behave like a black box, generating outputs without clear explanations.[2]

Without explainability:

Explainable AI (XAI) is now considered essential for healthcare systems — not a luxury.

If an AI system misdiagnoses a patient, who is responsible?

Current legal frameworks were not designed for autonomous or adaptive systems. This accountability gap is one of the most complex ethical issues in AI healthcare governance[6].

Healthcare datasets are highly sensitive. When AI models process millions of records, the risk of breaches increases dramatically.

Key concerns include:

Without robust privacy protections, trust collapses quickly.

If AI becomes too reliable, clinicians may gradually lose diagnostic or decision-making skills. This creates two dangers:

Human oversight must remain mandatory, not optional.

Advanced AI tools are expensive. If large hospitals adopt them while rural or underfunded facilities cannot, a two-tier health system may emerge. Ethical healthcare must ensure access is fair, not dictated by geography or wealth (1).

Watson aimed to revolutionise cancer care, but clinical evaluations later revealed inconsistencies and occasional unsafe recommendations[8]. Many insights were based on hypothetical scenarios rather than real patient data, highlighting the importance of real-world validation, transparency, and clinician oversight.

In 2017, the UK Information Commissioner’s Office ruled that patient data used for an AI-powered kidney injury detection project had been shared without proper patient consent[5]. Although the clinical goal was admirable, the lack of transparency damaged public trust.

On a positive note, AI systems for early detection of diabetic retinopathy have been successfully deployed in both low-resource and high-income settings (9). This represents AI at its best: validated, predictable, and targeted at a clear clinical need.

Good regulation protects patients without stifling innovation. Several global frameworks now shape AI governance in healthcare.

AI regulated as a medical device

The US FDA and the EU AI Act classify many AI tools as medical devices requiring strict evaluation and monitoring[6, 7]. HIPAA and GDPR protect sensitive healthcare data.

Continuous post-deployment monitoring

Because AI systems can drift over time, ongoing audits are essential.

Mandatory human oversight

Clinicians must remain the final decision-makers.

Transparency for patients

Patients should know when AI influences their care and understand its limitations.

Fairness audits

Algorithms must be tested across demographic groups to ensure equitable performance (4).

Ethical AI is not something you finish — it is something you continuously maintain, review, and improve.

Healthcare is ultimately a human experience. Technology can support it, amplify it, and streamline it — but it cannot replace its human foundation.

Trust between patient and clinician

Patients need reassurance that clinical judgement, empathy, and professional experience remain central to decision-making.

Trust in the healthcare system

Ethical, transparent AI adoption reinforces confidence that patient wellbeing comes first.

Trust that AI will enhance, not undermine, care (1)

When framed as a partner rather than a replacement, AI can genuinely strengthen healthcare delivery.

Patients will accept AI only when they believe it is safe, fair, transparent, and genuinely helpful. Fear and secrecy erode trust; openness and ethical grounding build it.

AI has the potential to reshape healthcare — improving diagnosis, accelerating research, and easing administrative burdens. But these opportunities come with serious ethical obligations.

A balanced approach — safeguarding privacy, ensuring fairness, clarifying accountability, and preserving the clinician’s role — is essential.

If healthcare leaders, policymakers, technologists, and clinicians work together, AI can help build a future where healthcare is more personalised, more efficient, and ultimately more humane.

Ready to take the next step in your NLP journey? Connect with top employers seeking talent in natural language processing. Discover your dream job!

Find Your Dream Job

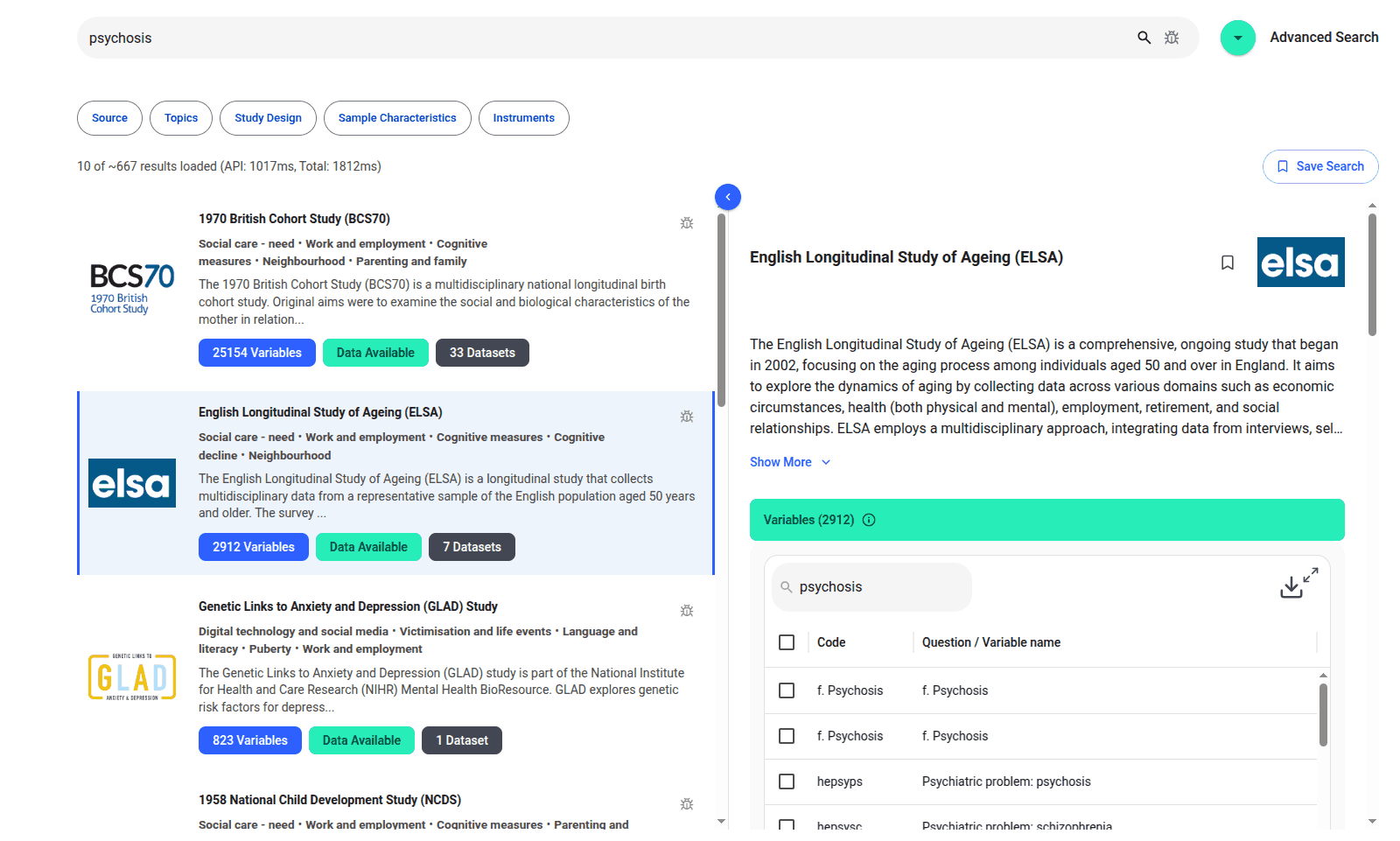

We are excited to introduce the new Harmony Meta platform, which we have developed over the past year. Harmony Meta connects many of the existing study catalogues and registers.

If you are developing an application that needs to interpret free-text medical notes, you might be interested in getting the best possible performance by using OpenAI, Gemini, Claude, or another large language model. But to do that, you would need to send sensitive data, such as personal healthcare data, into the third party LLM. Is this allowed?

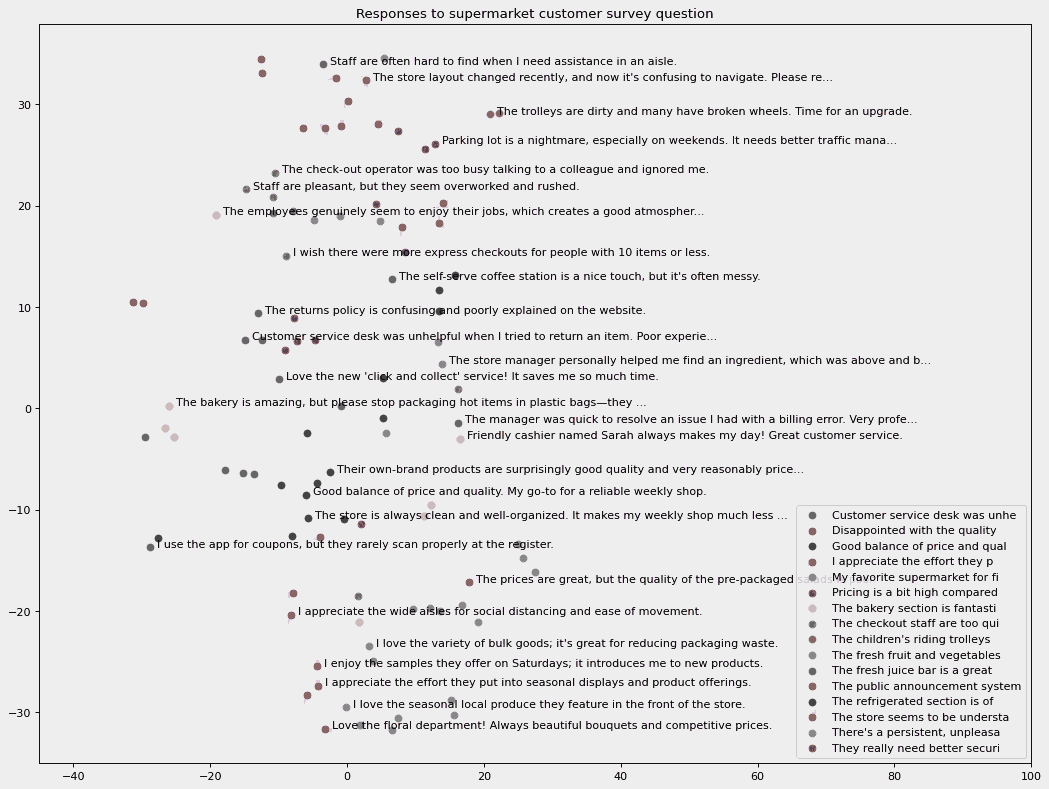

How can you use generative AI to find topics in a free text survey and identify the commonest mentioned topics? Imagine that you work for a market research company, and you’ve just run an online survey. You’ve received 10,000 free text responses from users in different languages. You want to quickly make a pie chart or bar chart showing common customer complaints, broken down by old customers, new customers, different locations, different spending patterns, and demographics.

What we can do for you