Is AI going to be a jobs killer? How many jobs will be lost to AI? What jobs will AI create?

According to a World Economic Forum report, automation will displace 75 million jobs by the year 2022, but it will also generate 133 million new jobs across the world. So AI will both destroy and create jobs.

A Gartner report claims that AI-related job creation will lead to the creation of 2 million net-new jobs by the year 2025.

In yet another report published by McKinsey Global Institute, there will be sufficient job creation by AI to balance the offset created by automation, as long as there is reasonably good economic growth, investment and innovation. However, some advanced economies may require additional investments to cut down the risk of job shortages. In the US at least, it is believed that net positive job growth will be seen up till 2030.

But amid this positive outlook there are also grim reports of how AI might lead to more job losses than job creation. An Oxford Economics report claims that as many as 20 million manufacturing jobs across the globe may be lost to robots and AI by the year 2030.

In mid-2019, Amazon made an announcement that it will invest $700 million into training approximately 100,000 US workers by 2025, to help them transition into more advanced jobs. The New York Times views this program as an acknowledgement by Amazon that automation technology advancements will take over most tasks that people are doing at the moment.

The studies above are just a small handful from a massive pool of reports, research papers, statistics and surveys which have observed how AI and machines will displace jobs in the not too distant future. In fact, Oxford academics Michael Osborne and Carl Benedikt Frey estimate that 47% of jobs in the US will likely be taken over by automation by the mid-2030s.

This isn’t the first time we’re hearing about machines, technology or AI making jobs obsolete because this has been going on for centuries.

A spinning jenny. Image source: Wikipedia

An elevator is an example of technology displacing jobs in the same way as AI today.

The spinning jenny, for example, replaced weavers, the internet made many travel agencies wind down business, and buttons made lift operators ‘obsolete’.

One study observed that between 1990 and 2007, 400,000 jobs in US factories were made redundant due to automation. Unfortunately, the trend as we know it today does not seem to be shifting – the drive to replace human workers with AI-driven ones is gaining momentum as companies struggle to combat the effects of COVID-19 while trying to keep operational costs as low as possible.

At the pandemic’s peak, the US shed approximately 40 million jobs, and while some have come back much to the delight of workers, some will likely never return. One group of economic experts believe that 42% of jobs shed are now gone forever.

With the global lockdown picking up pace again, this replacement of human workers with machines will likely pick up more speed. Companies are now shifting from ‘barely afloat’ mode to figuring out how they can keep their businesses thriving in the midst of the pandemic.

If you quickly recall the Gartner report mentioned at the beginning of the article claiming that AI will create 2 million new jobs by 2025 – well, ironically, a recently published paper by MIT and Boston University economists revealed that robots and AI may replace up to 2 million workers by 2025 in the manufacturing sector alone.

It’s easy to see why companies have taken this stance: the pandemic gives businesses a strategically strong reason to automate work that’s been traditionally done by people. Machines don’t need to take sick days, they don’t need to go into isolation to avoid spreading infection, and they don’t need days off from work – ever.

.](https://fastdatascience.com/images/sally-min-1.jpg)

Sally, a salad-making robot. Image source: Chowbotics.

It’s interesting to note how the deployment of robots was rapid in response to COVID-19. Robots could be seen cleaning up airport floors and even recording people’s temperatures. Universities and hospitals deployed Sally, a robot built by Chowbotics, which can make made-to-order salad – something only dining-hall employees could do previously.

Stadiums and malls have invested in Knightscope – security-guard robots to patrol and survey empty real estate, allowing remote security teams to react a lot faster when the need calls for it. Companies manufacturing hospital supplies like beds and cotton swabs have employed the services of Yaskawa America, a robot supplier, to help increase their supply.

There are many other examples, including one which has been heavily used as of late: chatbots to replace customer service agents. It’s probably safe to say that this trend of AI taking over and displacing jobs is the “new normal” – the pandemic merely accelerated and facilitated the transition, so to speak.

Now – in theory – artificial intelligence and automation should ideally free people from the dangers or repetitiveness of certain tasks so that perhaps they can divert their skills and talents towards more intellectually fulfilling and stimulating tasks. For one, this will certainly make companies more productive and even give them incentive to increase wages.

In the past, in fact, technology was deployed gradually, piece by piece, giving everyone ample time to adjust and transition into their new roles. And those whose jobs were lost could ask for retraining, or even use unemployment benefits or severance pay to quickly find work in a related field.

However, the same change this time has been very abrupt with employers rushing to replace workers with AI and software driven machines, in a bid to keep things moving amid the resurgence of COVID-19 and the imminent lockdown. Employers simply did not have the time or resources to retrain employees – AI-driven machines are much faster at learning and working tirelessly 24/7.

Fast Data Science - London

As an unfortunate consequence, companies whose bottom line was impacted the most since the pandemic, had to cut employees loose – employees who are now on their own and left to master new skills to stay employed. They came across few options, however.

Many countries in the past have responded to these rapid technological changes by investing in education. The US has been among these countries – when automation fundamentally altered farming jobs in the late 1900s, for example, the local states expanded access to public educational facilities. Access to college education post-WWII expanded between 1944 and 1956. However, the US investment in education has stalled since then, with workers finding it difficult to get educated on their own.

The idea of US education at the moment focuses on college education for young workers rather than providing retraining programs for experienced employees. And this is a key issue when it comes to AI and automation taking over jobs.

The real issue, you see, does not have much to do with a ‘rise of the machines’ or a robot apocalypse, but more about businesses retraining employees in an efficient, accessible, data-driven and well-informed way.

The next time you check into a hotel, don’t be surprised to see a mechanical butler rolling down the hall, delivering housekeeping items. Some hotels have even deployed robots to do a little meet and greet in their rooms before handing over a fresh pair of disinfected room keys.

This is all great, but it begs the question: Will AI eventually take over everyone’s jobs?

For centuries, many workers, from weavers to mill employees, have worried about technology making their job redundant one day – but that’s never proven to be true. ATMs, for example, did not lead to the bank tellers’ jobs getting hijacked. If anything, it led to more job openings for tellers since consumers, being lured by the convenience cash machines offer, started to visit banks more often.

Consequently, banks expanded branches and hired more tellers to look into tasks which ATMs were not capable of. Without the technological advancement that’s taken place, a large majority of the US workforce, for instance, would probably be toiling away on farms.

In the past, however, when there was even the slightest hint of automation eliminating jobs, companies would be quick to create new jobs to meet both their own needs as well as their workers’. For instance, manufacturers that were producing a higher volume of goods through machines would hire clerks to ship those goods and marketers to reach a higher number of target users.

But what’s happening today is that as automation makes it almost plausible for companies to hire fewer people – successful companies don’t even need to hire as many workers as they did a few years ago.

Just to give this some context, one of the most valuable US companies in the 1960s, AT&T, had over 758,611 employees, to be exact. The most valuable company in the US today, Apple, has only approximately 137,000 employees.

Even though today’s most successful companies across the US and UK make billions in revenue, they share it with a lot less employees than they did, and most of it goes into keeping shareholders happy. One look at Netflix, Google or Facebook – it’s easy to see that they are not creating more jobs within their companies that would require hiring people.

And you can’t blame them, really. Artificial intelligence today has become far more adept at doing jobs that were expertly done only by people – making it very challenging for workers to keep up with their AI counterparts.

JPMorgan is using AI to review commercial-loan agreements, completing what took lawyers 360,000 hours across 12 months, in just a few seconds. Recently, Microsoft laid off several journalists at Microsoft News and MSN, as they were replaced by AI capable of scanning and processing content effortlessly.

Some of the AI advances we’ve discussed above actually make it a no brainer for companies who are scrambling to absorb the effects of the pandemic and continue with ‘business as usual’. Municipalities that were left with no choice but to shut down their recycling operations (where peopled worked in close contact), are now using AI-assisted robots instead of humans to shuffle through tons of paper, plastic and glass.

The company making these robots, AMP Robotics, has reported that potential customer enquiries had massively increased between March and June 2020. In 2019, 35 recycling plants employed the services of AMP Robotics – the company’s spokesperson believes that almost 100 will do so by the end of this year.

In their defense, companies deploying AI technology claim that it enables them to create more jobs. However, this new AI-driven job creation isn’t too impressive compared to the jobs lost.

So, is the human workforce doomed?

Organizations are likely to continue leaning on technological advancements like AI to keep their businesses running as the pandemic forces them to reduce staff and make budget cuts. Many CEOs and Directors do not see themselves returning to former staffing levels because COVID doesn’t allow it.

According to IBM, AI adoption frees up people to undertake more nuanced and sophisticated job tasks. Swedish employers are pooling money in private funds to help workers get retrained. Singapore’s SkillsFuture retraining program reimburses residents by as much as 500 Singapore dollars – that’s $362 – for approved retraining.

In contrast, America’s most robust training programs are only for workers who are working overseas or have lost their job due to trade issues.

If we turn to history books, we can start to understand some of the fears and concerns around AI. They are very much real and understandable, but are they really warranted? Technological change has historically eliminated more jobs than it has created, but it has always created “more” in general – more for the company and its consumers, that is. But is this true across all industries?

Societal changes driven by technological change – like those resulting from automation and AI – spark feelings of fear, unrest and concern. And that’s justified, especially when you have studies like the 2-year one from McKinsey Global Institute suggesting that robots and ‘intelligent’ agents could replace 30% of the entire world’s labour by 2030.

The McKinsey study also suggests that in terms of sheer scale, the automation revolution as we know it could very well rival the shift away from agricultural labour which took place in the US and Europe in the 1900s – and more recently, the explosion caused by the Chinese labour economy.

But there’s more: McKinsey believes that according to how adoption scenarios might play out over the next few years – automation is going to displace 400-800 jobs worldwide by 2030 – requiring up to 375 million workers to switch their job fields altogether.

So we ask: how could a shift like this not strike fear, anxiety and uncertainty in the hearts of workers from vulnerable countries and demographic groups?

American research group, Brookings, suggests that if automations hits even 38% of the means of most forecasts, then Western democratic powers will likely turn to authoritarian policies to prevent civil chaos – which was exactly what happened during the Great Depression era.

It’s possible that, as a result, the US may start to look like Iraq or Syria – young armed bandits running around with hardly any employment prospects other than those related to war, vigilantism or violence. With such frightening yet authoritative outlooks like these, it’s no wonder the thought of AI ending jobs keeps people up at night.

Thus far, we’ve pondered over some of the potential upsides of AI adoption as well as some of the harrowing and potentially frightening downsides.

We should stop to think for a moment: Is the past really the best indicator of how new technology adoption might shape things up in future, job-wise?

At the peak of the Industrial Revolution, an increasing number of tasks were automated in the weaving process. This prompted workers to focus on other areas which technology was not capable of – such as manually operating a machine and then overseeing multiple machines to ensure they continue running smoothly. The end result? Total output increased massively.

In the US in the 19th century, the total volume of coarse cloth a weaver could produce per hour increased by nearly 50%, while the amount of labor required per yard of cloth decreased by 98%. Cloth got cheaper and demand went way up, with the total number of weaver jobs being quadrupled from 1830 to 1900.

So, new technology slowly changed the weaver’s job’s nature, as well as the skills needed to do it – and not replace it entirely.

We believe that technological change eliminates only certain kind of jobs, and the net job creation outlook in the process has always been positive.

But beyond this net job creation, there are actually a number of thought-provoking reasons which should set the tone for a half-full glass rather than half-empty;

Simply put, jobs which robots are doing now were not ‘good’ jobs to begin with. As humans, most of us are accustomed to going from physically demanding or mentally taxing and repetitive jobs at first – to eventually jobs which require the use of our grey matter, something which got us on top of the food chain to begin with.

By eliminating tedious jobs altogether, AI can free up workers to pursue other job skills and career avenues which gives them a greater sense of achievement and wellbeing. For example, jobs that challenge them, provide them with autonomy, a sense of forward progression, and make them feel like they’re really contributing to the economy – incidentally, attributes that make a job desirable and satisfying to do.

At a higher, more profound level though, AI can help eliminate poverty and disease from the world because it has already driven notable advances in the world of healthcare and medicine – more accurate diagnosis, improved disease prevention and ultimately, more effective treatments.

On the subject of ridding the world of poverty, AI can help eliminate barriers when it comes to identifying where aid is needed most urgently. If AI analysis is applied to data from satellite imagery, this barrier can be weakened or eliminated entirely, focusing aid towards those nations or areas where it is needed most direly.

When it comes to the impact of AI on jobs, the usual response filled with fear, dread and anxiety is often the result of what has happened throughout history when major technological changes were adopted. And that’s the first thing people tend to use as a yard stick for what’s to come.

But this approach might only make sense if the future behaves in a similar way. Today, there are many things which are done differently compared to the past – and this should be a good indication that the future too will play out differently.

In the past, for example, if one industry experienced a technological disruption, it did not necessarily mean that it would cause a ripple effect in other industries as well. In the case of auto manufacturing, for example – an AI-powered worker may be able to drive huge gains in terms of efficiency, speed and productivity. However, if you try to use the robot for anything other than manufacturing a car, it would be useless.

The underlying technology used in the robot can certainly be adopted, but that only addresses manufacturing needs and nothing else.

AI does not work like other technology disruptions because you can apply it to just about any industry whatsoever. When you learn to develop and adopt AI that understands languages, recognizes patterns easily, and knows how to solve problems, disruption is no longer contained.

Just imagine creating an AI technology that diagnoses diseases and prescribes medication, deals with lawsuits and writes insightful articles like this one! In fact, don’t just imagine – because AI is already doing these things as we speak.

One major distinction that we should understand between today and the past is the rate of technological progress – because this is something that advances exponentially and not necessarily linearly. Moore’s Law, anyone?

The number of transistors almost doubles every two years on an integrated circuit.

In the famous words of a University of Colorado physics professor,

The greatest shortcoming perhaps that we as a race suffer from is the inability to realize the exponential function.

Albert Allen Bartlett, emeritus professor of physics at the University of Colorado at Boulder, USA

We continue to underestimate what can happen when the value of something keeps doubling. AI may be a jobs killer, but it will also be a jobs creator, and who knows what jobs will be created by AI in the future?

Oliver Cann, Machines Will Do More Tasks Than Humans by 2025 but Robot Revolution Will Still Create 58 Million Net New Jobs in Next Five Years, World Economic Forum (2018)

Rob van der Meulen, Gartner Says By 2020, Artificial Intelligence Will Create More Jobs Than It Eliminates, Gartner (2017)

James Manyika et al, Jobs lost, jobs gained: What the future of work will mean for jobs, skills, and wages, McKinsey (2017)

Ben Casselman and Adam Satariano, Amazon’s Latest Experiment: Retraining Its Work Force (2019)

BBC, Robots ’to replace up to 20 million factory jobs’ by 2030 (2019)

Alana Semuels, What If Getting Laid Off Wasn’t Something to Be Afraid Of? (2017)

Ready to take the next step in your NLP journey? Connect with top employers seeking talent in natural language processing. Discover your dream job!

Find Your Dream Job

Senior lawyers should stop using generative AI to prepare their legal arguments! Or should they? A High Court judge in the UK has told senior lawyers off for their use of ChatGPT, because it invents citations to cases and laws that don’t exist!

Fast Data Science appeared at the Hamlyn Symposium event on “Healing Through Collaboration: Open-Source Software in Surgical, Biomedical and AI Technologies” Thomas Wood of Fast Data Science appeared in a panel at the Hamlyn Symposium workshop titled “Healing Through Collaboration: Open-Source Software in Surgical, Biomedical and AI Technologies”. This was at the Hamlyn Symposium on Medical Robotics on 27th June 2025 at the Royal Geographical Society in London.

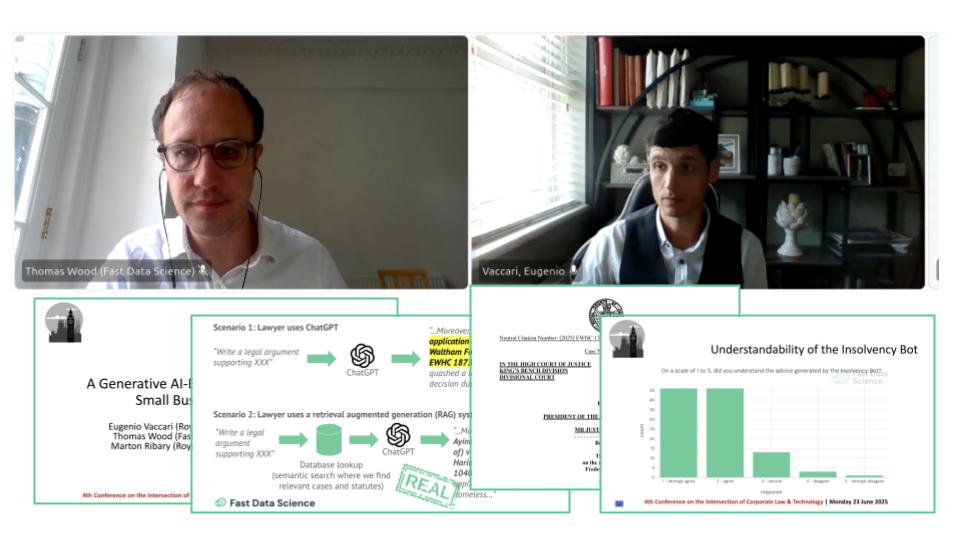

We presented the Insolvency Bot at the 4th Annual Conference on the Intersection of Corporate Law and Technology at Nottingham Trent University Dr Eugenio Vaccari of Royal Holloway University and Thomas Wood of Fast Data Science presented “A Generative AI-Based Legal Advice Tool for Small Businesses in Distress” at the 4th Annual Conference on the Intersection of Corporate Law and Technology at Nottingham Trent University

What we can do for you