In an earlier blog post, I introduced the concept of customer churn. Here, I’d like to dive into customer churn prediction in more detail and show how we can easily and simply use AI to predict customer churn.

Spoiler alert: there is no need to use an LLM! I don’t usually use much natural language processing for a customer churn project, because most data is stored in numeric fields such as transaction amounts. It’s not unheard of for some unstructured text data to be present in a customer dataset, but for the purposes of churn prediction, you will usually find all you need in numerical tables.

Customer churn is when you have a number of customers in your company and a certain number of them are likely to end their relationship with your company in the near future. Customer churn can be harmful to a business because of the lost revenue and the wasted money on acquiring that customer, as well as the fact that a churned customer may have switched to a competitor, may be dissatisfied, and might leave negative reviews. Customer churn may also indicate bigger problems: happy customers rarely leave, and a high churn rate could indicate a problem with your business’s offering.

Predicting customer churn can be challenging, whether you have small or large numbers of customers. But the value of accurately predicting churn can be huge.

We’ve recently taken on a number of customer churn prediction engagements for clients in retail, aerospace technology and other fields, and I’d like to distill what we’ve learnt from these in this article. I’d like to aim this article at business owners and managers in large B2C companies, as too many tutorials on this topic are aimed at beginners in data science and focus only on logistic regression, but have little practical advice around how to a customer churn model in a real business scenario.

Fast Data Science - London

Generally, machine learning becomes valuable for customer churn when you have very large numbers of customers, typically in a B2C context. If you have two or three customers each year, the numbers will be far too small for any meaningful pattern to show up. But thousands of customers are enough for there to be patterns that you can spot.

I’ve included some steps in a Python code repository so that you can follow along and try out the ideas I describe in this article: https://github.com/fastdatascience/customer_churn/blob/main/04_train_churn_model.ipynb

A customer churn project could be described as a lot of work joining tables, a little bit of easy work training machine learning models, and then a lot of hard work deploying your model to production.

Before getting started making an AI model to predict customer churn, we should first define the exact problem we want to predict either today or an arbitrary time in the future. We want to know something like:

which customers in the database are likely to cancel their subscription in the next month, given the information that we have about their ongoing subscription or relationship with our company and actions they have done in the past, but using no knowledge of actions that they will undertake in the future.

You can see that I have defined churn as “cancelling their subscription” in this case. This should be whatever easy-to-measure event that shows up in the data, which is closest as possible to what the company cares about: revenue. So your churn event could also be:

The important thing is that it should apply to all customers that we are analysing. If you have a mobile app, the frequency and nature of an event like “failure to renew” may vary between Play Store and Apple Store because of how subscriptions on those platforms work, so that may not be an adequate event to measure.

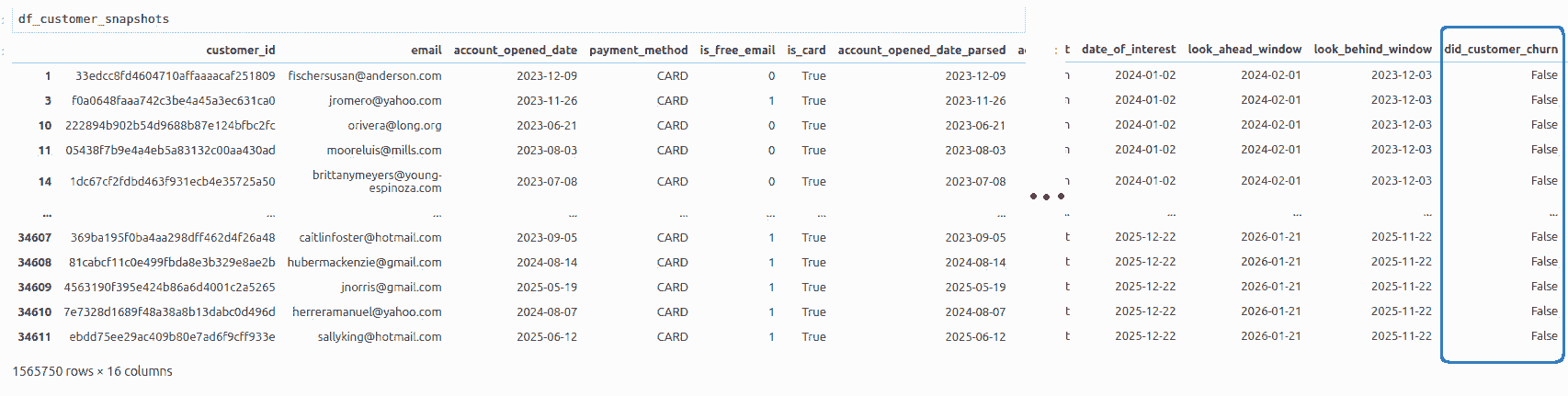

You need to also clearly define the time window in which that event occurs. In my accompanying example notebook on Github, I am using a 30-day lookahead to see if the account will be closed within 30 days of any date of interest. I’m also using a 30-day look behind to sum all transactions before that date of interest, which is an input feature into my model.

You’ll notice that I mentioned “given the information that we already have”. This may seem obvious but it’s important to formalise what knowledge we already have about a customer, because when we train our machine learning model, we will use knowledge of what was known at points in the past. It’s important to draw a clear distinction between the past and the future.

For example, the user’s home city in the database may not be a good feature to put into any machine learning model, because the user may have updated their address and the address now is not the one that was in the database a year ago. Likewise, if we want to use the “total spend by user” as a feature, we need to be able to reconstruct what the “total spend” was at a given date in the past - it’s no use if you only know the total spend now.

The training data will consist of a lot of “readings” of the state of a customer at various time points in the past, and events that happened before those time points - and one event that happens after, namely the churn event (a binary variable).

In an ideal case, you will have two or more years of data to train your customer churn model on.

If you are running your model at the beginning of 2026, I would suggest using all of 2024 as training data and all of 2025 as test data. A complete year of data encompasses all seasonal patterns in your industry. If the model trained on 2024 can reliably predict what will happen in 2025, then it’s likely to remain robust for predictions going forward.

You also want to define the time frame on which you will predict the customer churn. For example, do you want to predict if a customer will churn in the next week, month or year? This is a choice that you can make according to what time frames are important for your business. In general, you will achieve a higher accuracy and better performance metrics if you predict in the short term, such as a week. But you may have more data to work with if you train models to predict in the long term like a year.

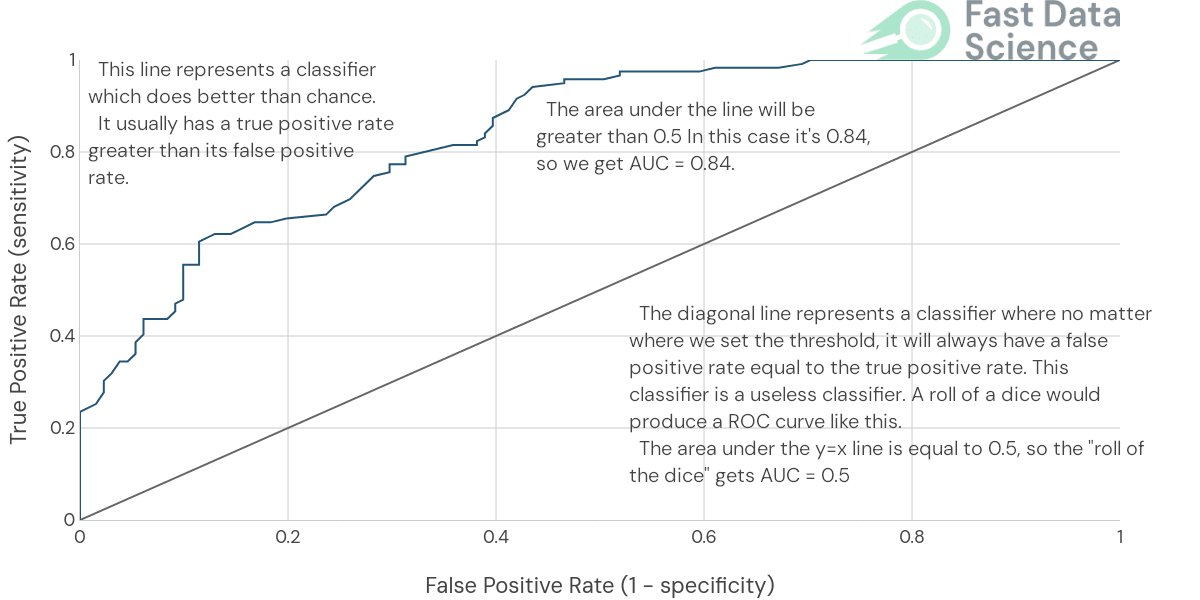

Rather than using accuracy, I would use the area under the ROC curve (AUC). The AUC is a very useful metric for binary classification, and our churn is a binary outcome. It’s far more useful than using accuracy because in the real world, only 5% of your customers may churn in the relevant time period, so a model which predicts “retention” as an outcome 100% of the time would achieve a 95% accuracy, which would sound good even though it would be completely useless.

The ROC (Receiver Operating Curve) is a plot of true positive rate against false positive rate for a range of sensitivity thresholds in the model. A completely random model (roll of the dice) would achieve a 50% AUC, a model which gets everything perfectly wrong would achieve a 0% AUC, and a perfect model would achieve 100%.

In a customer churn project in a business setting, I would consider that 70%-80% would be a good result and quite possibly a ceiling of what’s achievable. Remember, we are predicting the action that a person will take in the future, humans are inherently unpredictable, so in some senses it’s amazing that we can predict anything at all!

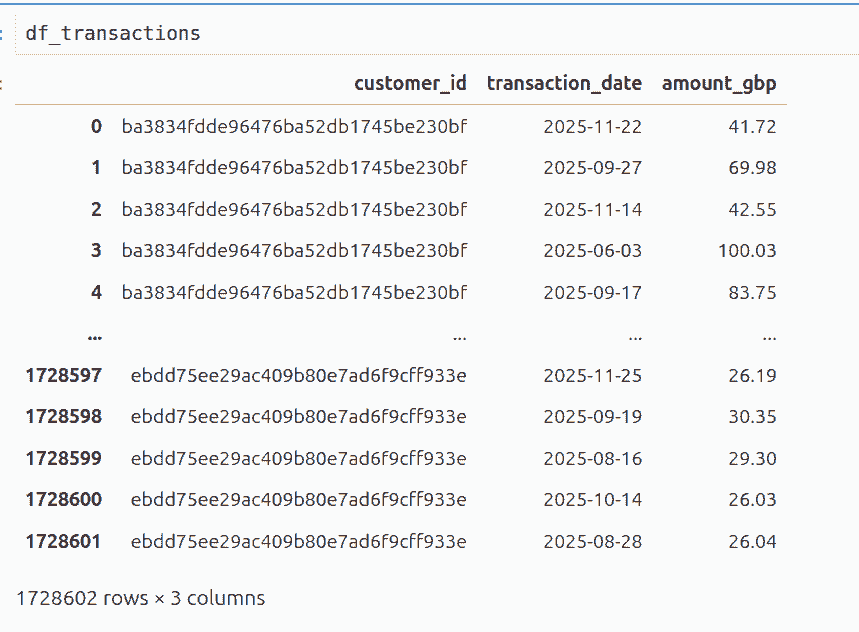

I would assume that you have a database table of customers containing key information such as demographic size and address, subscription type, payment type, and so on. This is your core database table that you will use for joining to other tables. Usually a large amount of relevant data can be obtained by joining your customer table to tables of transactions, or other interactions with a customer.

For example, every purchase may be recorded in a transactions table, and every interaction on the website may be recorded in a web analytics table. Let’s assume that in our case you have a customer table, a transactions table, and a web analytics table. For each customer, at any point in time, you can calculate things like the total spend until that date, the number of transactions in the past week, the number of website visits in the last week, and so on.

Your machine learning model needs an input table of the form below, where the x_i are the features that you know about a particular customer at a particular point in time (your independent variables) and the y is the churn (your dependent variable).

| x_1 | x_2 | x_3 | … | y (did the user churn in the next month) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 12 | 21 | 64 | … | 0 |

| 2 | 5 | 2 | … | 1 |

| … | … | … | … | … |

This has to be a flat table. So before you go anywhere near machine learning, you need to spend some time gathering data about the “state of your knowledge about a customer” at a time in the past, and condensing it into a single table.

If you have 100 customers, and 10 time points, you will then have 100 * 10 = 1000 rows in your joined table.

| date that we are looking at | customer ID | transactions in last week | total spend to date | website visits in last month | … | y (did the user churn) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2 January | 4674 | 12 | 21 | 64 | … | 0 |

| 3 January | 6873 | 2 | 5 | 2 | … | 1 |

| … | … | … | … | … | … | … |

Joining and building this table correctly is 90% of the work involved in building the initial churn model (excluding deployment of the model, which is its own massive headache and which will come later!).

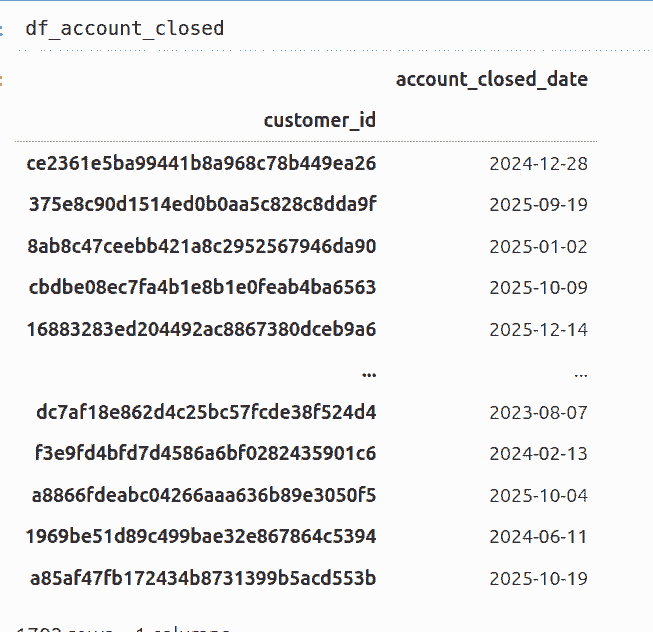

In my walkthrough example on Github, we have a customers table, a transactions table, and a table for accounts closing.

They look like the tables below before joining. In the walkthrough, we will join them using Pandas, but in practice you would try to join them on your database using SQL Join commands of some kind, if possible.

It’s sometimes the case that the data is split across systems, for example, a web analytics system, Salesforce, and a finance system. In those cases you will definitely need to harmonise and join the data yourself, and the data cleaning will be hard work.

After joining, we get a very wide and very long table, where every row corresponds to an active customer at a particular date of interest in the past, and contains our outcome did_customer_churn (whether the customer churned within 30 days of the date of interest). Doing this join can take a long time, and if the resultant table is too big for your computer to handle, you may want to sample it.

In every customer churn project I have worked on, the highest performing algorithm has been either a random forest model or XGBoost model.

These models are useful because they are very good at handling data with weird distributions, they can learn patterns involving complex interactions between features, and you don’t need to put in too much work cleaning up your features.

For example, it’s quite possible that you have 100 customers who spent around £10 and one single customer who spent £10,000. If you were to use a linear regression model, effects from that one giant customer will dominate the behaviour of the entire model, and you’ll end up with an inadequate model that performs badly on the £10 and the £10,000 customers. With a random forest model, you don’t have this concern.

For the purposes of this discussion we don’t need to understand exactly how a random forest model works, but suffice to say that the model contains a huge number of smaller models with their own parameters, can be very large and slow, but can handle more complex relationships between variables than simple correlations.

Now that you have joined your data, you can do a train-test split. Traditionally in machine learning you may have heard about using a randomised 80-20 split over all your data points. However at this point I would suggest to split your data over time, so your model is trained on data seen before 1 January 2025, and tested on data afterwards.

Why should we split the data over time instead of using randomisation over a consistent time period? Won’t our model be susceptible to changes in market conditions, seasonality, and macroeconomic factors?

Answer: Randomised splits tend to give over-estimates of the model performance. It’s hard to prevent leakage of data between your training and test sets. So you need to be certain that no customer ever affects both your train and test sets. Also, the testing process should be as close as possible to the real world scenario that we want to run the model in. In the real world we have a clear cutoff between the past and the future. If we can show that our model was robust against macroeconomic trends from 2024 to 2025, we hope that the same approach will allow us to keep predicting into 2026 and beyond.

I would then train a random forest model on the training dataset, and use it to predict the churn on the test dataset. I would take the probability prediction from the model, and plot a ROC curve and measure the Area Under the Curve (AUC).

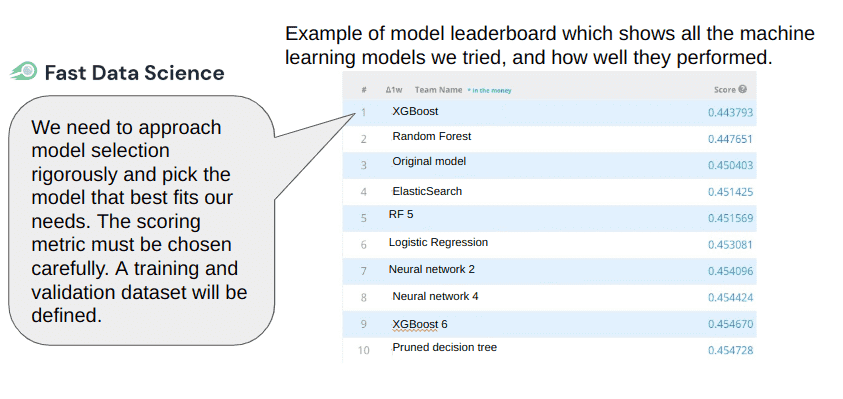

I would also try this with and without the analytics tables, adding and removing features, and keeping track of the effect on the AUC. I would usually train an iterative series of models, starting from the simplest, and each time adding more and more useful data, but always evaluating performance on the same test set. I number these experiments expt_01, etc, and often go through around 40 or 50 models, recording scores in a leaderboard, before choosing a winner.

You will see over time that the AUC will gradually improve until it hits a ceiling and stops going up, even when you add more features. Hopefully you will have achieved an AUC of somewhere around 70% or 80%.

Once you have trained and tested your model, I recommend looking inside it. A random forest model will provide “feature importances” which let you see which features have been the most informative. This will be useful as it may help you understand the mechanisms behind the churn. For example, maybe a customer submitted a complaint or raised a ticket with support, and that feature is the #1 predictor of churn.

I suggest also to plot some graphs showing the breakdown of different variables and things like the overall probability of churn given that the user paid with card vs other payment methods. This is really informative, and graphs help you uncover all kinds of patterns that you would otherwise miss. For example, for one customer, it was clear that users who pay with Apple Pay are unlikely to renew their subscription - the reason is that Apple Pay doesn’t allow apps to auto-renew paid subscriptions without user interaction, so renewal rates will naturally be lower on Apple Pay than via other payment platforms.

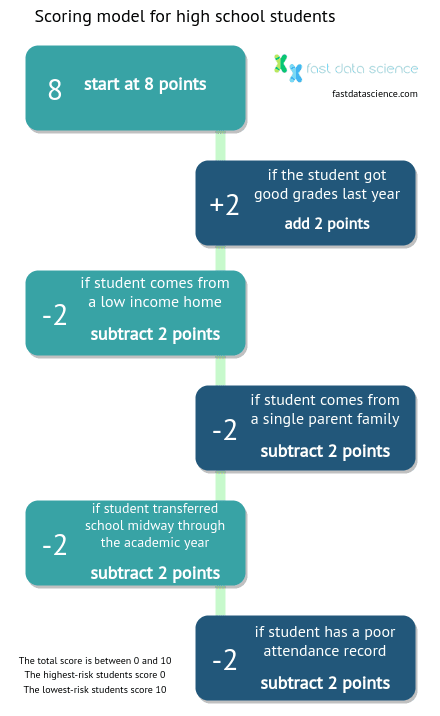

I am a big fan of also going back to basics and making a human-readable scoring model which can be used by a human even with pen and paper to quickly score a customer.

Knowing what you know from the random forest model about the informative features, you can pick the best features, probably engineer them a little (for example, if there is one customer who spent £10,000, you can create a feature for total spend capped at £100, so that outliers don’t disrupt your model too much), and put them into a Logistic Regression model.

You can then take the coefficients from the logistic regression model and normalise them to a scale of 100. Then you can create a recipe for scoring a customer like

1.20

+ num_transactions_in_last_30_days_capped_at_10 * 13.51

+ spend_in_last_30_days_capped_at_100 * -1.20

+ is_free_email * 55.87

+ is_card * 29.11

+ days_since_last_transaction_capped_at_30 * 0.31

This makes a score whose maximum is 100 (very likely to remain) and minimum is 0 (very likely to churn). Something like this is great for gaining a intuitive understanding of what is driving churn.

You should also calculate your AUC for the linear model. I would expect it to be better than chance (i.e. over 50%) but not perform as well as the random forest model.

Now that you’ve trained on 2024 and evaluated on 2025, I would suggest to make a new final production model trained on both 2024 and 2025, which can be used for future predictions. This is a little harder to evaluate but you could hold out a tiny bit of 2025 data to evaluate it. The reason is that you are now using all of your data to make the final predictive model.

After training the final predictive model, you need to make some predictions on the current customer database.

You will probably need to write some SQL queries to get the state of all customers at the current moment in time. This will be very similar to the queries used to gather your training and test data, but adjusted slightly because we’re interested in the current state of those customers rather than reconstructing known information at a particular date in the past.

You can then create a table of predictions looking something like this:

| customer id | probability of churn |

|---|---|

| 129875 | 0.92 |

| 687216 | 0.91 |

| … | … |

If you sort the customers by probability of churn, you can quickly identify those customers that you need to focus a retention effort on.

Now that you’ve identified the customers who are likely to churn, what can we do about it?

Predicting the probability of churn doesn’t tell us anything about causality (in fact causality is a very difficult thing to model accurately). But I would suggest trying a few interventions on the customers that we know are likely to churn, to see if there’s anything we can do to influence them.

For example, we can take the 1000 most likely to churn customers and split them randomly into two groups of 500 people each, which we will call “control” and “treatment”. We can send the 500 people in the treatment group a voucher offering a 50% discount, and the 500 control group receive nothing. This approach is called an A/B test (you can read more in our article on A/B testing).

If the group was on average 90% likely to churn, we would expect 450 people in the control group to churn in our time period. If the voucher causes the churn rate to drop to 80% in the treatment group, we would have retained 50 extra customers, and the extra retention would have just covered the money lost by offering the 50% discount.

Before running an A/B test like this, take a while to sit down and think about how many customers you might expect to retain with the voucher, and use an A/B test calculator to estimate the sample size that you’d need in order to get any useful information out of the experiment.

If the A/B test is effective, you could consider rolling out the discount strategy across all customers as a regular business process. Now we’re talking about model deployment.

In addition to running the A/B test, you can also learn from the random forest model’s feature importances. For example, if churns are highly correlated with complaints, you would want to look into what those complaints are telling you. Maybe there is a particular product line that leaves customers very dissatisfied. There will be a wealth of business insights that you can gather from the churn model and use to guide a customer retention strategy. Perhaps, instead of the A/B test, you could call up the customers who are likely to churn and try understand if their needs are not being met.

In my experience, deploying a model is at least as much work as all the model development and data engineering work that we’ve done up to this point.

You will need to write and deploy batch jobs to pull out your features from the company database on a regular basis, run the model, and take whatever action is needed from the model’s predictions, all without human intervention.

There are a huge number of things which can go wrong here, so you’ll need to set up monitoring to check that the model is still running without errors, check that it’s not emailing too many people, and of course, keep monitoring how many people redeem the voucher.

Deployment will need coordination between your data science and engineering teams, as well as some outlay for hosting infrastructure.

You may also want to set up a regular job to re-train your model as more data comes in, although I would generally prefer only to train models manually, as any unsupervised training process has far too many things that can go wrong.

The choice of time period should be whatever is most relevant for the company. Ask yourself, if you were the CEO, is it better to know who will churn in the next year, or the next month? You can always predict both. A time period that is too short will make it hard to train a machine learning model because of data sparsity. For example, if you have 10,000 customers and only 4 churners, that is too little data to learn any meaningful patterns, so you should choose a time period where a significant proportion of customers churn anyway.

In general your endpoint that you are trying to predict, is will customer #12312 be active on [date]. If they leave and re-enter it doesn’t matter, the main thing is will they be still an active paying customer on the date that you care about.

Your prediction will always be a probabilistic prediction, e.g. you give customer #12312 a 89% churn score. You can never be completely sure if that cusomter will churn or not. We are predicting a customer’s most likely action (churn vs retain), not their mindset. We cannot see inside their mind.

If your business is not a subscription business, you will need to use a definition of churn that is applicable to your case. For example, if you have a bakery and people buy every day, but then someone doesn’t buy for a month, you could consider that person to have churned. You will have to choose a time window that is appropriate for the business as your definition of churn.

A lot of the time you will find in a customer churn project that there is only quiet churn, rather than an official churn event that occurs at a well defined point in time. Only in a subscription based business would you see users actively doing something that constitutes a churn event, such as cancelling their Amazon Prime subscription. But even with a subscription model, a user will churn if they don’t put a valid card on the account when the current card expires, so there are still churn events that aren’t marked by a subscription cancellation. If you work a subscription based business which charges annually, and 6 months into a term a user stops logging in, you could consider the churn event to be at that point, rather than at the first point in time 6 months later that the user declines to renew.

However, cancellations and non-renewals are the easiest things to measure, so you might be better off working with those if they are available in your context.

On one project that we worked on, I built a machine learning model to predict whether a student at a higher education college will stop coming to classes. We have data on each student such as whether they come from a single parent family, their household income, and their past grades, and their home address. Looking at thousands of students, you can see the patterns. Students who have poor grades and a low income background tend to be more likely to quit.

But when a student stops coming to class, they don’t tell the teacher or school. They just stop turning up (we could call this “quiet quitting”). If the student doesn’t show for a week and they haven’t informed anyone they are sick, we consider them to have quit. Students won’t officially un-enrol from classes (unless a payment is due). So churn in an educational institution is something that you will have to define.

We can contrast the student churn example with predicting employee churn. We worked on a project to predict employee turnover in the NHS. You would expect that for predicting employee churn, you will have a “churn event” which is the point that the person ceased to be an employee of a company. However in this context, we had to define churn as “absence from the payroll for more than 6 months”, because of the way the dataset was structured.

Any kind of business which relies on repeat or regular customers will want to improve customer retention and reduce churn. If you are a business which makes one-off sales (imagine an ice cream vendor in a tourist hotspot) then it may be less relevant.

Subscription businesses will predict churn by training a model in the way I described in the blog post above and in the example code: take all customers at time t, and track them until time t+δt. If 90% are still active at time t+δt, then train a model to classify between these two classes (ACTIVE vs INACTIVE), based only on the information which was available at time t. This task is much simpler for subscription based businesses than non-subscription based businesses.

Predicting customer churn is not difficult, but the lion’s share of the work involves gathering data from different tables and joining it together. My recommendation is to approach customer churn as a binary prediction problem and build a random forest model. You may have to think carefully about your definition of “churn” if there is not a single clear cut churn event that you can use, such as a user cancelling their subscription.

I also recommend using a temporal split (training on the past to predict the future), rather than the random split into training and test data that we usually use in machine learning.

If you would like to learn more about customer churn, or have a customer churn problem in your business, please get in touch with me.

You may also be interested in my earlier post and videos on predicting customer spend and predicting employee churn.

Unleash the potential of your NLP projects with the right talent. Post your job with us and attract candidates who are as passionate about natural language processing.

Hire NLP Experts

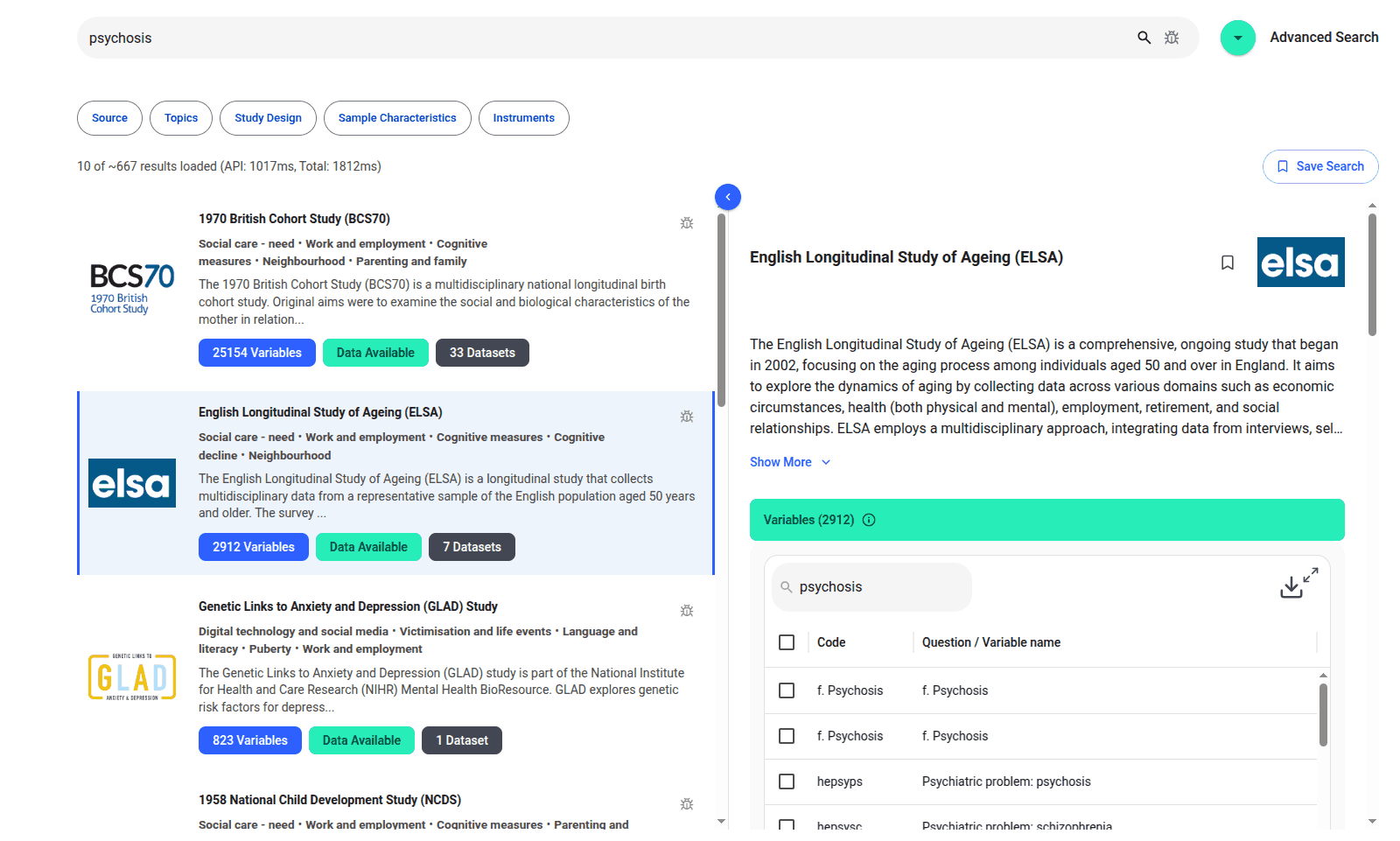

We are excited to introduce the new Harmony Meta platform, which we have developed over the past year. Harmony Meta connects many of the existing study catalogues and registers.

Guest post by Jay Dugad Artificial intelligence has become one of the most talked-about forces shaping modern healthcare. Machines detecting disease, systems predicting patient deterioration, and algorithms recommending personalised treatments all once sounded like science fiction but now sit inside hospitals, research labs, and GP practices across the world.

If you are developing an application that needs to interpret free-text medical notes, you might be interested in getting the best possible performance by using OpenAI, Gemini, Claude, or another large language model. But to do that, you would need to send sensitive data, such as personal healthcare data, into the third party LLM. Is this allowed?

What we can do for you