The AI ethics debate: does generative AI harm creative industries? What role will AI play in creative industries in the future?

Artists are worried that DALL-E could put them out of a job. Creative writers are raising the alarm about ChatGPT. Hollywood actors are worried about their voices being cloned. Before long, a similar debate could arise about AI-generated music.

What is not clear at the moment, is whether large generative AI models are harming those in creative professions, or if they are merely the latest iteration of tools that creative humans have at their disposal. There are a number of other widely discussed topics in AI ethics, from AI bias to autonomous weapons, but the advent of generative models in the last year has already begun to reshape the creative industry.

At the touch of a button, ChatGPT can generate a blog post, or DALL-E can create a graphic. Those who would otherwise have hired a freelancer can now use natural language processing and AI for free. A recent investigation by NewsGuard found 49 “news” sites that appear to be almost entirely written by AI.

The book illustrator Chris Mould pulled out of the Bradford Literature Festival when it emerged that AI was used to generate its publicity images.

…how can I stand under their roof and tell people they can go to art school and work in these disciplines, if the material used to publicise that event is generated at the push of a button?

Chris Mould

Mould is objecting to AI art on the grounds that it cheapens art, that is, it replaces human labour with an automated process.

The Australian artist Jazza has posted an interesting dissection and critique on his YouTube channel of an art book which he deduced was AI generated:

But there is another more subtle issue with AI generated art. Generative models do not exist in a vacuum of pure algorithms. They need human artists to work. GPT-3 was trained on a dataset of nearly a trillion words, all written by… humans! DALL-E was trained on a similar enormous dataset of images including original artwork. OpenAI acknowledge this on their website:

“reproducing training images verbatim can raise legal questions around copyright infringement, ownership, and privacy (if people’s photos were present in training data).” Source: OpenAI blog

What we can do for you

Generative AI isn’t just about churning out realistic images. It can be used for powerful creative purposes:

This showcases the potential of generative AI to not just replicate, but to inspire and create entirely new visual concepts.

The debate around generative AI and creative industries is only just beginning. While some fear it as a job killer, others see it as a powerful tool for creative expression. As with any new technology, the key will be using it responsibly and ethically to augment human creativity, not replace it.

In 2024, OpenAI said it would remove one of the voices used by ChatGPT, after the Hollywood actress Scarlett Johansson complained that it was too similar to her voice. Johansson claimed that OpenAI had contacted her, asking her permission to use her voice in the product, and she declined, and OpenAI included it anyway.

In this case, Johansson hired legal counsel, and OpenAI withdrew the voice from their product. It is unclear exactly whether Johansson’s voice was used to train OpenAI’s model, or whether the resemblance was coincidental, but it is precisely this plausible deniability which creatives are worried about.

In a time when we are all grappling with deepfakes and the protection of our own likeness, our own work, our own identities, I believe these are questions that deserve absolute clarity

Scarlett Johansson

The crux of the ethical question we face around generative models should not be the effect they have on supply and demand. In any case, when has it ever been possible to restrict a new technology because it puts people out of work? Even if one country legislates about this, companies will find a way.

We should be focusing on the right of the artist to control the use of their artwork for training AI models. Since the beginning of the digital age, artists have had to worry about others stealing their work. They can mitigate the risk of this happening by watermarking work, restricting access through technology, or through copyright laws.

So, if an artist can restrict others from copying their work without consent, what about using it to train an AI without their consent? Unfortunately this appears to be a legal grey area. The tech company Stability AI created an AI art tool called Stable Diffusion, which was trained on images taken from the internet, including from stock photo libraries such as Getty Images.

Getty Images has commenced legal proceedings against Stability AI in the High Court of Justice in London, alleging copyright violation and violation of their website’s terms of service. Update from November 2025: the High Court has ruled mostly in favour of Stability AI in this case.

In 2023, I went to the Financial Times Future of AI Summit in London, and I was interested to watch a presentation by a speaker from one of the stock photo libraries, who said that AI image generation is simply “the latest disruptor in our industry”. Analogue photography to digitisation was a previous disruptor, and generative AI is the next wave. Stock content providers specialising in original content had to adapt to previous disruptive technologies and this opinion leader believed that they can survive this change.

The visual media companies are not sitting on the sidelines. Many formerly traditional content providers have made their own generative AI models, with some limitations that set them aside from the best-known big players in generative AI:

This ensures they avoid copyright issues and stay clear of ethically murky territory. The training data underlying these generative models wasn’t scraped from the internet, but was already obtained commercially by the content providers.

Even IP lawyers are unsure of how the AI/creative industry lawsuits will develop. On both sides of the Atlantic, the outcomes of the initial cases will affect the future landscape of AI art and generative AI’s impact on creative industries. In particular, copyright law defines fair use, derivative works and transformative works.

If you ask an AI to generate music in the style of the Rolling Stones, when their music is in its training dataset, would this be considered a derivative work? After all, depending on how it is calibrated, AIs can and often do spit out exact instances from their training dataset.

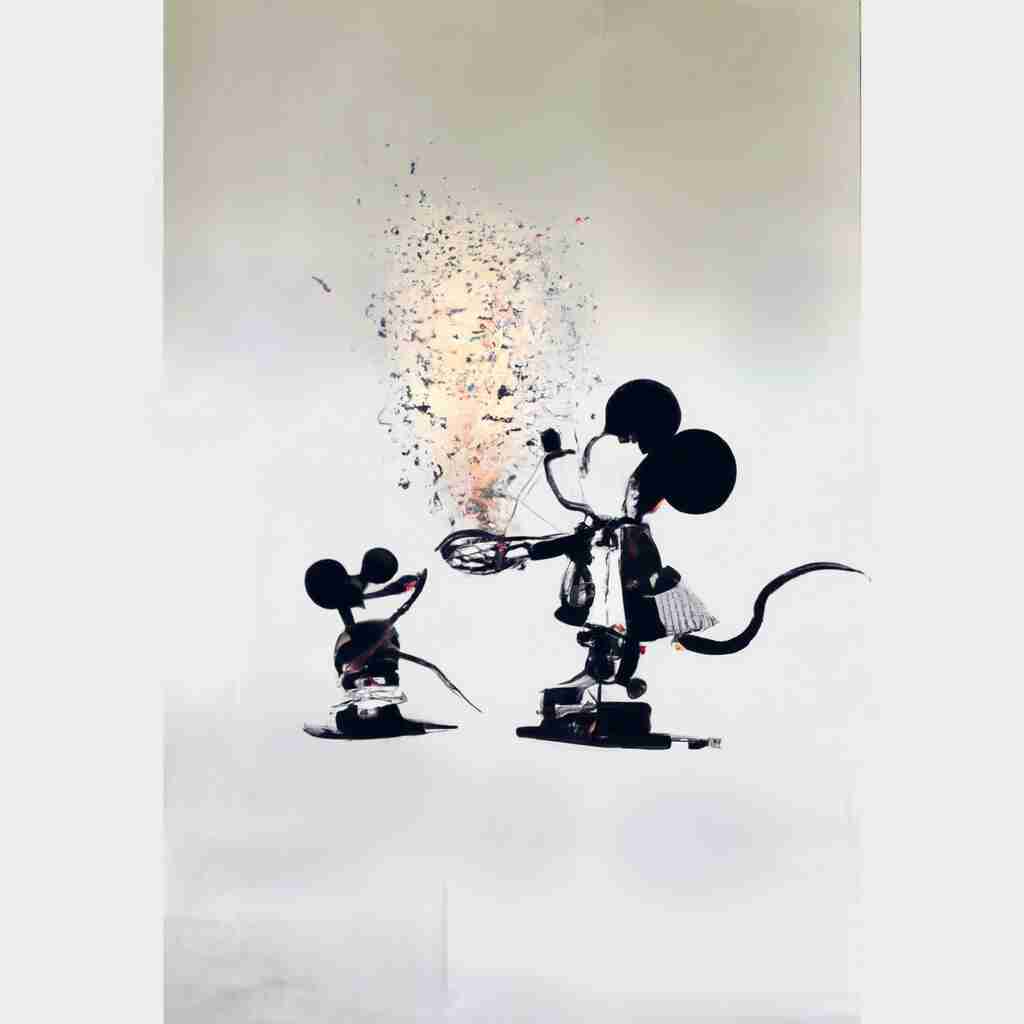

I asked DALL-E to generate me an image of Mickey Mouse in the style of Banksy, and it gave me the following, indicating that both Disney-copyrighted images, and Banksy’s artwork, must be in its training set.

There are some lower-key alternatives to DALL-E which market themselves as taking a more ethical approach to artists’ rights. However, I do not envisage grassroots startups and non-profits making a significant change to the landscape without the budget of the big tech giants (the cost of training GPT-3 has been estimated to be between $4.6 million and $12 million).

Perhaps artists need to have the option to attach a license to their work, stating “I do not consent for this work to be used for training an AI model”. Or the default for any creative work could be an opt-in system, where only explicit consent counts.

I expect that in the next few years, after the first big civil cases, the dust will settle and the issue will become clearer to everyone what constitutes fair use of an artistic work and what role AI will play in creative industries.

Interestingly, the concept of copyright did not begin in the digital age, but began much earlier, with the British Statute of Anne 1710, titled “An Act for the Encouragement of Learning, by vesting the Copies of Printed Books in the Authors or purchasers of such Copies, during the Times therein mentioned”. In essence, the arrival of the printing press in Europe allowed popular books to be easily copied.

Now, generative AI has created a new challenge for artists and writers, and legislation will need to catch up.

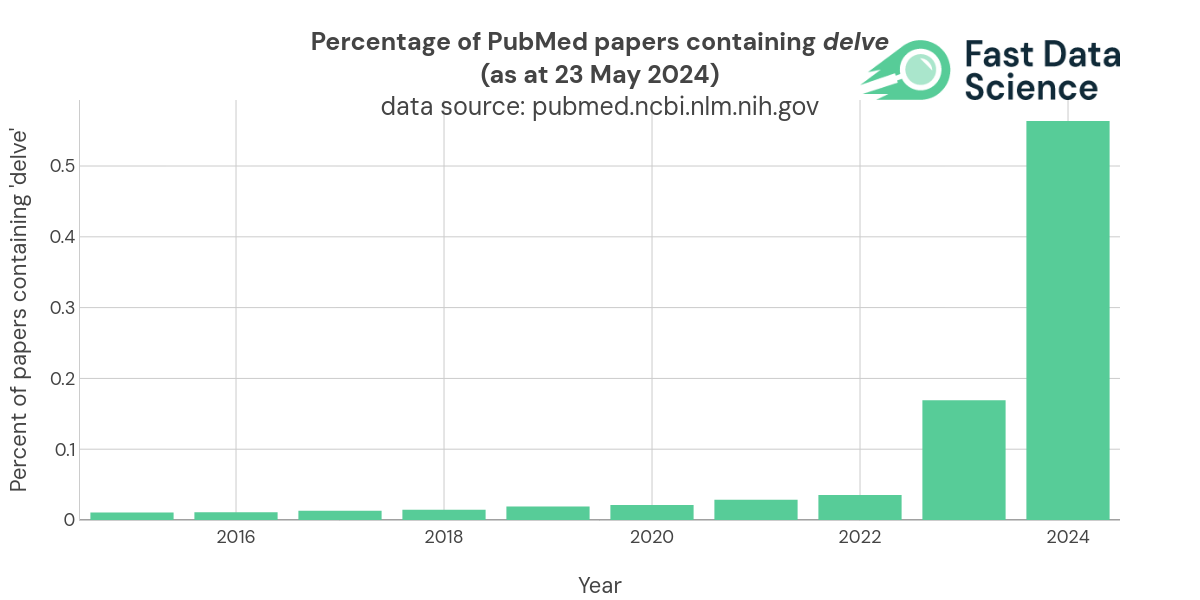

GPT has attracted attention because it is quite trigger happy with certain words such as ‘delve’. By 2024, nearly one in 200 papers on PubMed contained the word ‘delve’.

I have tried to use generative AI for content writing. Its output is mediocre at best, a distillation of the content of the internet at the date its training data was harvested. I view machine learning models as a generalisation of a kind of averaging (the simplest machine learning model possible is to take the mean of a set of numbers - this is a regression model with one single parameter).

In my view, a generative AI does not really create content, but synthesises and averages the existing content. I think for that reason a portion of the hysteria around generative models is somewhat unjustified.

Ready to take the next step in your NLP journey? Connect with top employers seeking talent in natural language processing. Discover your dream job!

Find Your Dream Job

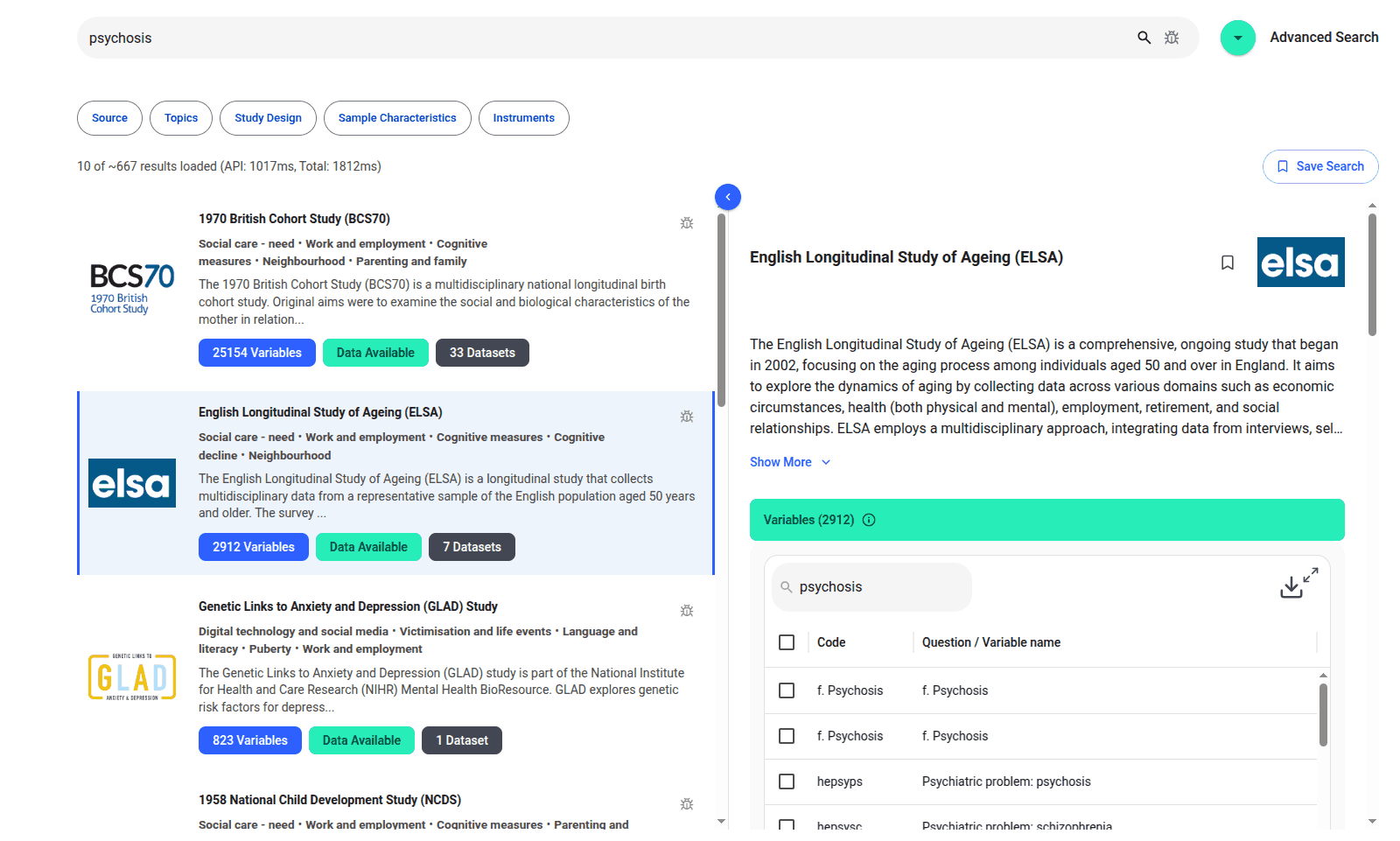

We are excited to introduce the new Harmony Meta platform, which we have developed over the past year. Harmony Meta connects many of the existing study catalogues and registers.

Guest post by Jay Dugad Artificial intelligence has become one of the most talked-about forces shaping modern healthcare. Machines detecting disease, systems predicting patient deterioration, and algorithms recommending personalised treatments all once sounded like science fiction but now sit inside hospitals, research labs, and GP practices across the world.

If you are developing an application that needs to interpret free-text medical notes, you might be interested in getting the best possible performance by using OpenAI, Gemini, Claude, or another large language model. But to do that, you would need to send sensitive data, such as personal healthcare data, into the third party LLM. Is this allowed?

What we can do for you