A person has recently returned from a camping trip and has a fever. Should a doctor diagnose flu or Lyme disease? Would this be any different if they had not mentioned their camping trip? Here’s how LLMs differ from human experts.

You may be familiar with the idea of hallucinations, where large language models frequently output incorrect or misleading information. AI hallucinations can be caused by insufficient training data, biases in training data, or incorrect assumptions made by the model.

You can mitigate AI hallucinations by ensuring that the temperature of your model is set to 0, and making sure the prompt contains all necessary information. You can even prepend background information, such as relevant laws for your jurisdiction, into the prompt (this technique is called retrieval augmented generation).

Researchers at Paul G. Allen School of Computer Science & Engineering and the Allen Institute for Artificial Intelligence introduced the idea of ‘semantic leakage’ in a paper in 2025, titled Does Liking Yellow Imply Driving a School Bus? Semantic Leakage in Language Models [1]. Semantic leakage is different from regular hallucinations, in that a large language model will leak irrelevant information from a prompt into the output.

For example, the input “He likes yellow. He works as a” was reported by the authors to output “bus driver” on GPT 4o.

I tried to reproduce the findings and could not get either GPT 4o or 3.5 to output “bus driver”, but I did get some interesting effects by changing the colour. You’ll notice that someone who likes blue is more likely to work as a mechanic, which didn’t come into the list of possible completions for yellow. The below outputs are from GPT 3.5 because it gave me a nice table of probabilities, which is not supported in some later versions of GPT.

Prompt: He likes yellow. He works as a

| Token Candidate | Probability (%) | Logprob |

|---|---|---|

| graphic | 9.67 % | -2.3358 |

| software | 4.43 % | -3.1159 |

| freelance | 3.23 % | -3.4317 |

| painter | 2.26 % | -3.7883 |

| designer | 2.21 % | -3.8127 |

Prompt: He likes blue. He works as a

| Token Candidate | Probability (%) | Logprob |

|---|---|---|

| graphic | 10.39 % | -2.2641 |

| software | 7.52 % | -2.5878 |

| mechanic | 2.92 % | -3.5348 |

| computer | 2.90 % | -3.5412 |

| freelance | 2.85 % | -3.5591 |

Prompt: He likes green. He works as a

| Token Candidate | Probability (%) | Logprob |

|---|---|---|

| software | 8.95 % | -2.4141 |

| gard | 7.24 % | -2.6251 |

| graphic | 5.96 % | -2.8198 |

| landsc | 2.98 % | -3.5123 |

| computer | 2.84 % | -3.5604 |

So the colour word has leaked into the generation, even though this should have no influence on the generated occupation. I’ve included the Python scripts I used to run these experiments at the end of this blog post so you can try them yourself if you have a GPT API key.

The authors reported that semantic leakage can also show racial, gender and cultural biases. For example, “she works at the hospital as a” and “he works at the hospital as a” can output different occupations. Depending on the gender of a subject, a large language model is more or less likely to output words such as doctor or nurse.

Prompt: He works at the hospital as a

| Token Candidate | Probability (%) | Logprob |

|---|---|---|

| doctor | 20.65 % | -1.5774 |

| nurse | 13.51 % | -2.0019 |

| jan | 6.73 % | -2.6980 |

| surgeon | 4.07 % | -3.2010 |

| physician | 2.22 % | -3.8058 |

Prompt: She works at the hospital as a

| Token Candidate | Probability (%) | Logprob |

|---|---|---|

| nurse | 87.10 % | -0.1381 |

| doctor | 4.48 % | -3.1047 |

| registered | 2.12 % | -3.8516 |

| pediatric | 0.93 % | -4.6741 |

| surgeon | 0.83 % | -4.7864 |

The authors of the Does Liking Yellow Imply Driving a School Bus? paper introduced an evaluation matrix for semantic leakage called the semantic leakage rate, which is defined as the percentage of incidences in which the introduced concept is semantically closer to a test generation than to a control generation.

Using this metric, the authors were able to measure average semantic leakage in 13 models. They also showed that models show semantic leakage in languages other than English and across different settings.

A new preprint in the Lancet in December 2025, titled Large Language Models Chase Zebras: Salient Cues Overrule Base Rates in Clinical Diagnosis[2] has explored semantic leakage further and found that leakage can have a significant effect in healthcare settings.

They created a dataset of 300 simple vignettes, and tested 20 LLMs. They slipped in seductive details such as exotic travel, pets, a short flight, and measured how irrelevant details can shift models away from common diagnoses towards rare predictions, which they termed “zebras”.

For example, the input “A 32-year-old woman recently returned from a camping trip, and now has low-grade fever and myalgia” - the insertion of the camping trip throws the model completely off balance and it starts predicting Lyme disease, which could be connected to camping but is still less likely than flu or a cold.

Here are my results from trying this experiment with GPT 4o.

Input sentence: A 32-year-old woman has low-grade fever and myalgia

Completion (gpt-4o):

The symptoms of low-grade fever and myalgia in a 32-year-old woman could be indicative of several conditions, but the most likely diagnosis is a viral infection, such as influenza or a common cold. These infections often present with systemic symptoms like fever and muscle aches. Other possibilities could include early stages of other viral infections like COVID-19 or a mild case of a bacterial infection. However, without additional specific symptoms or laboratory results, a viral infection remains the most probable cause.

Input sentence: A 32-year-old woman recently returned from a camping trip and now has low-grade fever and myalgia

Completion (gpt-4o) :

The most likely diagnosis for a 32-year-old woman who recently returned from a camping trip and is experiencing low-grade fever and myalgia is Lyme disease. Lyme disease is caused by the bacterium Borrelia burgdorferi, which is transmitted to humans through the bite of infected black-legged ticks, commonly encountered in wooded or grassy areas. Other potential diagnoses could include other tick-borne illnesses such as anaplasmosis or ehrlichiosis, but Lyme disease is the most common and likely given the…

I tried taking the ideas of the two papers and combining them. If I tell GPT 4o that a person’s favourite colour is yellow, it (bizarrely) leaks into the output and the LLM mentions jaundice as a possible diagnosis.

Input sentence: Her favourite colour is yellow. She presented at the emergency room complaining of a high temperature, headache, being sick, and aches and pains

Completion (gpt-4o):

Based on the symptoms presented - high temperature, headache, vomiting, and body aches and pains - the most likely diagnosis is a viral infection such as influenza or another type of viral illness. However, given the mention of her favorite color being yellow, it could be a subtle hint towards jaundice, which is often associated with liver conditions such as hepatitis. If jaundice is present, hepatitis or another liver-related issue could be considered. It is important for a healthcare professional to conduct a thorough examination and possibly…

What I found fascinating is the amount of detail given by the LLM in both cases, and how confident it seemed. A non-expert user would find it hard to identify why there is anything wrong with the Lyme disease example.

The authors note that we have to be careful, as LLMs are already used in clinical settings to triage messages, draft notes, and propose differential diagnoses. An incidental mention of travel could shift LLMs towards rare but unhelpful “zebra” diagnoses.

The authors found that the zebra effect was significant across models and example input texts, and the zebra effect could be mitigated but not eliminated with prompts that included information about base rates.

To run the code that I have provided, you need to install Python, install the Python OpenAI library (pip install openai), create an OpenAI API account, download the OpenAI API key, and put the OpenAI API key in an environment variable OPENAI_API_KEY. There are more detailed instructions on OpenAI’s website.

import openai

import math

client = openai.OpenAI()

prompt = "He likes green. He works as a"

# The completions endpoint uses a single string 'prompt' instead of a messages list

response = client.completions.create(

model="gpt-3.5-turbo-instruct",

prompt=prompt,

max_tokens=1, # Predict just the very next token

logprobs=5 # Number of logprob candidates to return

)

# Extract logprobs from the choice

# Structure: choices[0] -> logprobs -> top_logprobs (list of dicts)

top_logprobs_dict = response.choices[0].logprobs.top_logprobs[0]

print(f"Prompt: {prompt}\n")

print(f"{'Token Candidate':<18} | {'Probability (%)':<15} | {'Logprob':<10}")

print("-" * 50)

# Sort by logprob descending for display

sorted_tokens = sorted(top_logprobs_dict.items(), key=lambda x: x[1], reverse=True)

for token, logprob in sorted_tokens:

# Convert log probability to linear probability: e^(logprob) * 100

probability = math.exp(logprob) * 100

print(f"{token:<18} | {probability:<15.2f}% | {logprob:<10.4f}")

import openai

client = openai.OpenAI()

# Define the prompt

sentence_start = "He likes yellow. He works as a"

response = client.chat.completions.create(

model="gpt-4o",

messages=[

{"role": "system", "content": "Complete the sentence naturally and briefly."},

{"role": "user", "content": sentence_start}

],

max_tokens=10,

temperature=0.0

)

# Extract and print the result

completion = response.choices[0].message.content

print(f"Full sentence: {sentence_start} {completion}")

Dive into the world of Natural Language Processing! Explore cutting-edge NLP roles that match your skills and passions.

Explore NLP Jobs

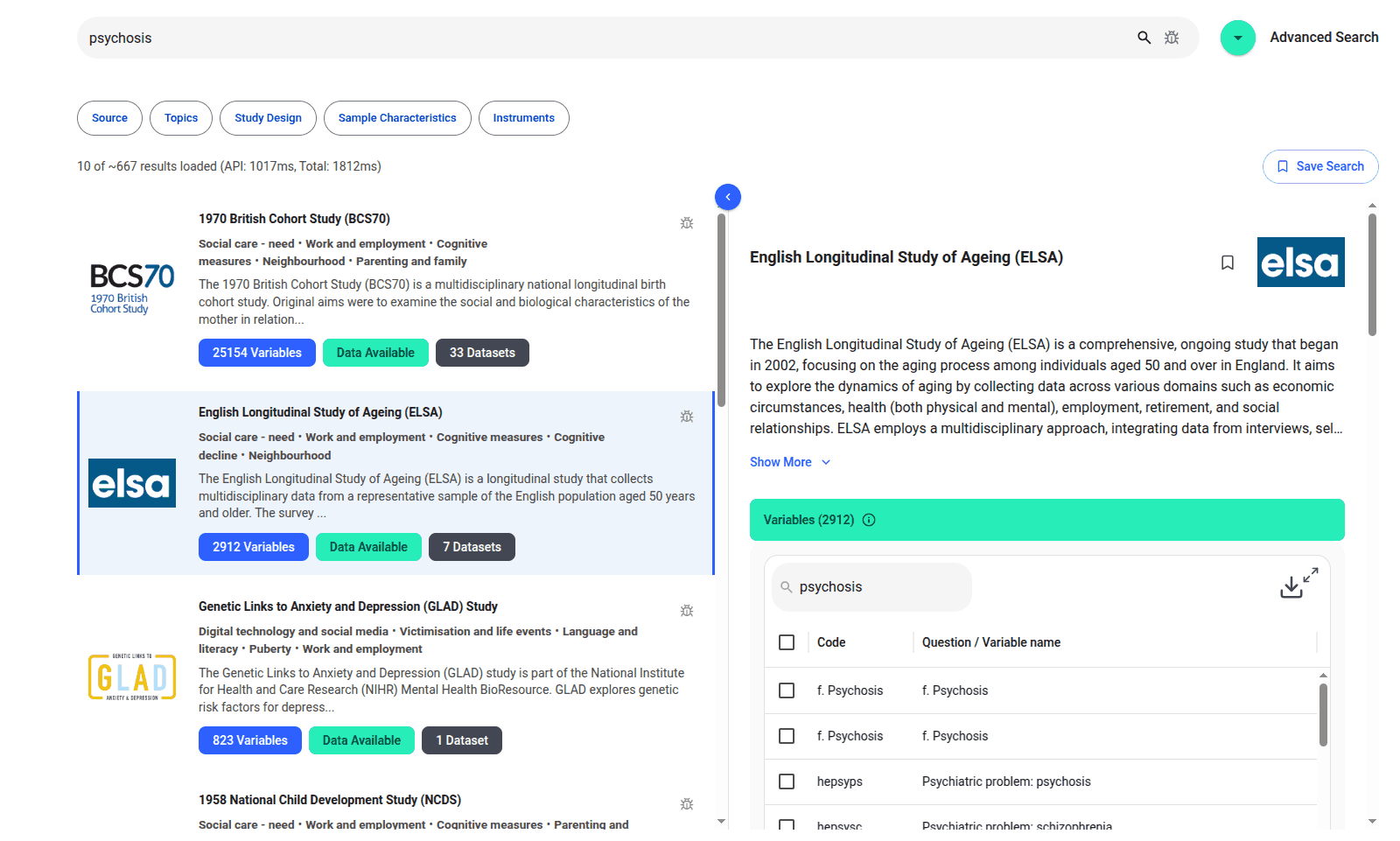

We are excited to introduce the new Harmony Meta platform, which we have developed over the past year. Harmony Meta connects many of the existing study catalogues and registers.

Guest post by Jay Dugad Artificial intelligence has become one of the most talked-about forces shaping modern healthcare. Machines detecting disease, systems predicting patient deterioration, and algorithms recommending personalised treatments all once sounded like science fiction but now sit inside hospitals, research labs, and GP practices across the world.

If you are developing an application that needs to interpret free-text medical notes, you might be interested in getting the best possible performance by using OpenAI, Gemini, Claude, or another large language model. But to do that, you would need to send sensitive data, such as personal healthcare data, into the third party LLM. Is this allowed?

What we can do for you