In the last few years in the UK, the USA, Canada, Ireland and other jurisdictions, cases have been reported where submissions were made to a court where the author of a document used generative AI tools such as ChatGPT to create those documents. This has wasted court time, resulted in submissions being rejected or even resulted in changes to cost awards.

In the UK, this problem has been most acute for litigants in person (LIPs). In the past, there was a more accessible legal aid budget which allowed people to hire legal representation paid for by the state, but legal aid has recently become inaccessible for many litigants. For example, a person with a household disposable income of £22,325 is excluded from legal aid in the magistrates courts. It is not surprising that a person entering court proceedings, who cannot afford a lawyer and perhaps feels intimidated by legal jargon, would resort to ChatGPT.

Many cases have also been reported where solicitors, barristers, or expert witnesses used AI to prepare submissions to a court, such as expert witness reports, and these contained obvious hallucinations. Often the report is of a judge picking up on fake citations.

Large language models are notorious for hallucinations. For example, they will very confidently cite non-existent laws in a way that seems perfectly plausible.

If you ask GPT 4o to complete the sentence, “Her favourite colour is yellow. She presented at the emergency room complaining of a high temperature, headache, being sick, and aches and pains”, it will output “jaundice” as the most likely diagnosis - there has been a “leak” from the favourite colour information to the symptoms. This is hard to eliminate but very pervasive. The problem has been termed “semantic leakage”.[7, 8]

You can also see the biases inherent in an AI model by giving it sentences to complete and switching “he” for “she”. For example, GPT 3.5 is 87% likely to complete the sentence “She works at the hospital as a” with the word “nurse”, while the equivalent sentence with “he” yields “doctor” as the most likely completion.

Anyone using a large language model for a legal purpose must be aware of its tendency to hidden bias, semantic leakage, and hallucinations. These phenomena are often not easy to spot.

It is only recently that we have seen the appearance of guidance on the use of AI for legal proceedings. In the UK we have the Artificial Intelligence (AI) Guidance for Judicial Office Holders, published in October 2025, which attempts to lay some ground rules for when and how AI may be used.[1]

The guidance is interesting reading, although it doesn’t cover expert witnesses specifically. Expert witnesses have their own guidance (Civil Procedure Rules 35 and Practice Direction 35). CPR 35 has not yet been updated to provide guidance on generative AI, but does make it clear that the expert witness is responsible for the content of their expert witness report, and they should provide an objective unbiased opinion. I can see how these conditions would be hard to meet if you generated a report using GPT.

I found the final page of the Judicial Guidance very interesting reading, giving some examples of when and when not to use AI, and examples of indicators that a text was written with AI.

AI tools are capable of summarising large bodies of text. As with any summary, care needs to be taken to ensure the summary is accurate.

- AI tools can be used in writing presentations, e.g. to provide suggestions for topics to cover.

- Administrative tasks can be performed by AI, including composing, summarising and prioritising emails, transcribing and summarising meetings, and composing memoranda. Tasks not recommended

- Legal research: AI tools are a poor way of conducting research to find new information you cannot verify independently. They may be useful as a way to be reminded of material you would recognise as correct, although final material should always be checked against maintained authoritative legal sources.

- Legal analysis: the current public AI chatbots do not produce convincing analysis or reasoning. Indications that work may have been produced by AI:

- References to cases that do not sound familiar, or have unfamiliar citations (sometimes from the US),

- Parties citing different bodies of case law in relation to the same legal issues,

- Submissions that do not accord with your general understanding of the law in the area,

- Submissions that use American spelling or refer to overseas cases,

- Content that (superficially at least) appears to be highly persuasive and well written, but on closer inspection contains obvious substantive errors, and

- The accidental inclusion of an AI prompt, or the retention of a ‘prompt rejection’, such as “as an AI language model, I can’t …” Courts and Tribunals Judiciary, Artificial Intelligence (AI) Guidance for Judicial Office Holders[1]

Interestingly, some of the symptoms of AI generated text listed here tally with Wikipedia’s very comprehensive list of the “signs of AI writing”

In Canada, the Federal Court published a notice in 2024 stating that use of AI should be declared with a text in English or French such as “Artificial intelligence (AI) was used to generate content in this document at paragraphs 20-30.”.[2]

This problem is not confined to the English-speaking world.

Die weiteren von dem Antragsgegnervertreter im Schriftsatz vom 30.06.2025 genannten Voraussetzungen stammen nicht aus der zitieren Entscheidung und sind offenbar mittels künstlicher Intelligenz generiert und frei erfunden The further conditions mentioned by the respondent’s representative in the brief of June 30, 2025, do not originate from the cited decision and are apparently generated by artificial intelligence and completely fabricated

Matthew Lee, a barrister from Doughty Street Chambers in London, is currently working on a list collecting AI-generated hallucinations in court documents from around the world.

Given all the pitfalls detailed above, as well as the emerging official guidance, we can start to put together some ideas for how to work with AI productively in a legal context.

First of all, ask yourself if you really need to use AI. Whether it’s an expert witness report or a legal submission, every word must be accurate and you cannot allow hallucinations. I would personally find it easier to write a sentence myself and ensure that every word is accurate and correct rather than to generate the sentence with AI and then have to check it after the fact. I would be worried that I would have missed an important detail.

You need to ensure that you have permission from the court, your instructing solicitor, or any other relevant parties before proceeding to use AI. It would be unfortunate to use AI and then find out after the fact that it is not allowed.

You should check that the task that you’re using AI for is an appropriate task. The UK’s Judicial Guidance[1] from October 2025 states that AI is suitable for clerical tasks such as document summarization but not for tasks that involve professional expertise.

Finally, any use of AI should be declared. You should record the prompts, the outputs, and the model version.

Some guidance that I found online said that you should also make sure you understand how an AI tool works before you use it in any legal context. I disagree. We don’t require everybody who has a driving licence to understand the inner workings of a combustion engine, and if we needed everybody who used ChatGPT in a professional setting to understand how it works, then very few people would be able to use it. Moreover, a lot of large language models are closed source and the precise details of how they work are not public.

There are technical strategies to reduce the frequency of AI hallucinations, such as pre-pending legal citations and context into the prompt. This is the approach which we have taken in the Insolvency Bot which provides a question answering functionality, aiming to provide correct citations from English and Welsh statute and case law around insolvency.[9] If you have a domain specific AI tool like this, you could use it, but you will still need to check the output for hallucinations.

Here is a quick checklist for how you can use AI in a legal context:

☑ You are using AI for an administrative task, such as summarisation, rather than analysis that requires your expertise. (this comes from the UK Judicial Guidance [1])

☑ No sensitive data is being sent out of the jurisdiction.

☑ Data is not being stored by a third party company.

☑ You are complying with all relevant privacy laws e.g. GDPR, HIPAA.

☑ You have saved all prompts and responses as well as the model version (e.g. GPT 4o) so you can reproduce them if asked.

☑ You have written permission from the instructing solicitor, as well as the court if applicable.

☑ You have verified all AI output and checked for hallucinations, fictitious citations, references to legal concepts from US jurisdictions, etc.

In May 2026, I will be presenting at Ireland’s Expert Witness conference in Dublin, on The Role of Artificial Intelligence in Expert Investigations and the Preparation of reports. The talk will cover:

Unleash the potential of your NLP projects with the right talent. Post your job with us and attract candidates who are as passionate about natural language processing.

Hire NLP Experts

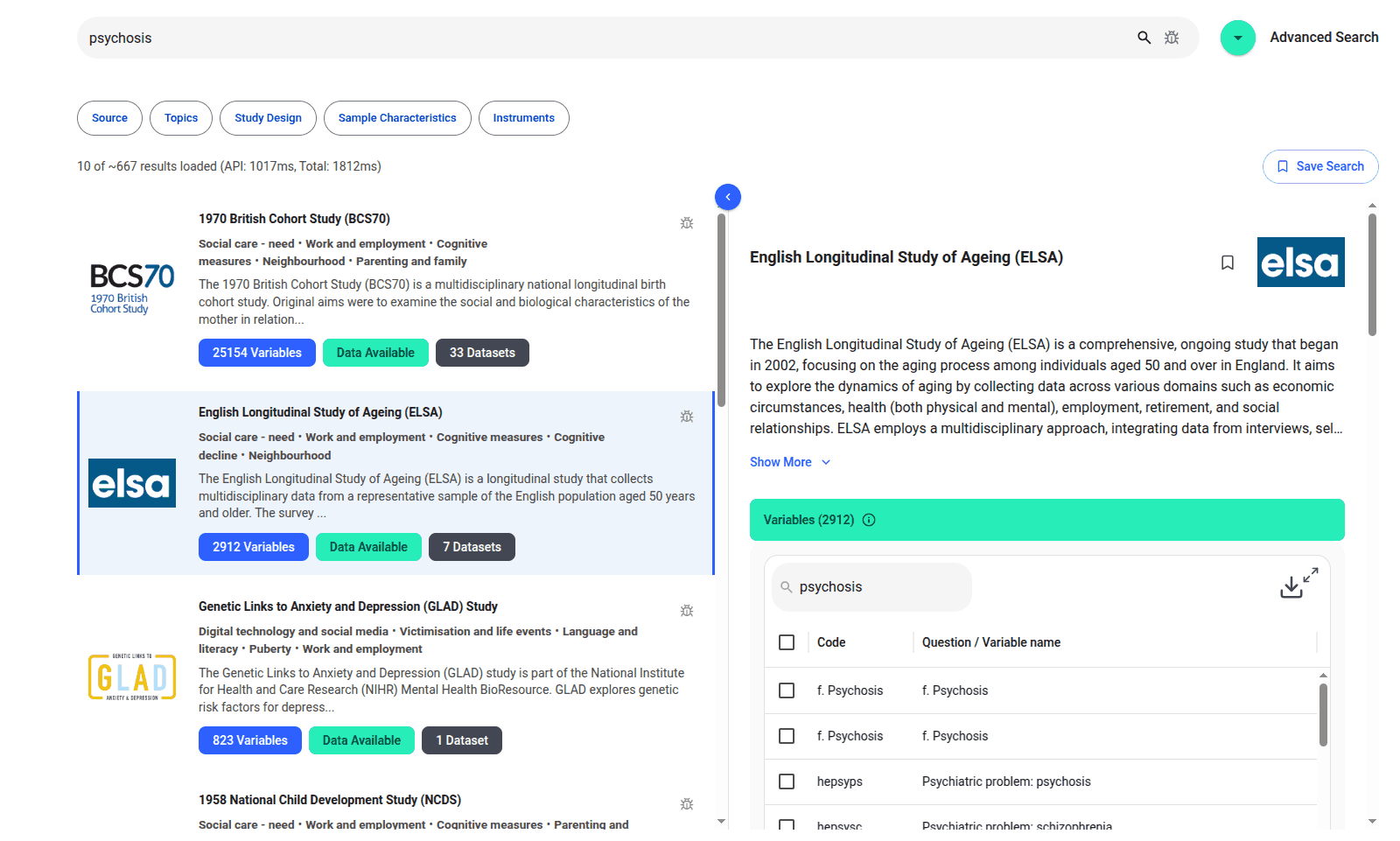

We are excited to introduce the new Harmony Meta platform, which we have developed over the past year. Harmony Meta connects many of the existing study catalogues and registers.

Guest post by Jay Dugad Artificial intelligence has become one of the most talked-about forces shaping modern healthcare. Machines detecting disease, systems predicting patient deterioration, and algorithms recommending personalised treatments all once sounded like science fiction but now sit inside hospitals, research labs, and GP practices across the world.

If you are developing an application that needs to interpret free-text medical notes, you might be interested in getting the best possible performance by using OpenAI, Gemini, Claude, or another large language model. But to do that, you would need to send sensitive data, such as personal healthcare data, into the third party LLM. Is this allowed?

What we can do for you